In 1903, the Wright Brothers invented the world’s first successful airplane. Just 13 years later, Robert Goddard launched the world’s very first liquid fueled rocket, a technology that would develop into the incredible machines we have today. These flying machines all have one thing in common, to many, they seemed like an iimpossible dream at first – like something that simply defied the laws of physiscs. But airlplanes quickly became routine and eventually took over the entire world.

Fast forward to 1965 when Soviet cosmonaut Alexei Leonov became the first human to float freely in space, performing the first spacewalk. Protected by nothing other than a rope and a spacesuit, Alexei experienced the scale of the Earth in a way that no one ever had before. But it wasn’t until two decades later that humans would really fly in space.

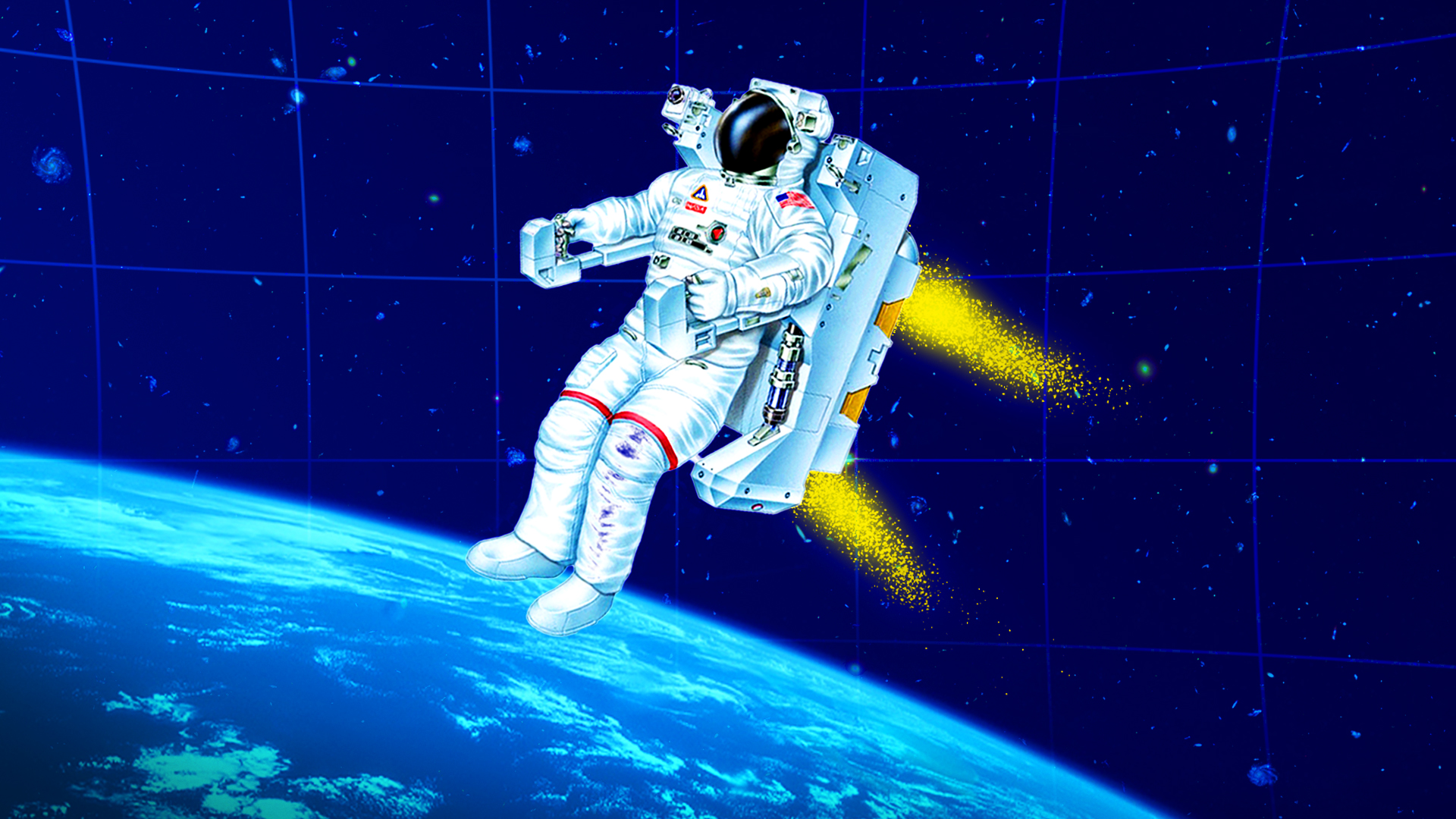

The Manned Maneuvering Unit

In order to give astronauts more mobility during spacewalks, NASA developed a new machine called the MMU or manned maneuvering unit. This was essentially a giant jet pack with onboard thrusters, which would allow astronauts to easily move around their spacecraft and future space stations. Before, astronauts had to remained tethered to their spacecraft, making it difficult to move around the whole spacecraft without tethering to different points. Early designs of the MMU were in development since the early 60’s, expecting to be used during the Gemini missions. But it wasn’t until 1984 that the jetpack was first used to fly an astronaut in space.

The challenges of a spacewalk

Even by the mid 80’s, spacewalks were no easy task. The mental and physical challenges required to do an 8 hour spacewalk were enormous. The spacesuits required to keep them alive were incredibly stiff. Since they were inflated like a big balloon, it created a lot of resistance against their movements. Making a good space suit is still one of the hardest challenges in spaceflight, since the joints in the suit that allow our arms and legs to bend become completely rigid due to the pressure difference.

To add to this, astronauts weren’t allowed to have a lunch break during the spacewalk – so they relied solely on drink bags inside of their helmets to keep them going. So while the jetpack wouldn’t make space walks an easy task, the idea was to give the astronauts more freedom and allow them to move without straining their muscles. It would also allow astronauts to go out and retrieve and repair broken satellites, a concept very attractive to NASA at the time.

Steering the jetpack

The jetpack itself was shaped like a large backpack, which would attach onto the life support system on the astronaut’s spacesuit. It featured two large aluminium tanks, each containing 9kg of nitrogen. This nitrogen would be used as the propellant for the 24 thrusters placed around the jetpack.

These were cold gas thrusters which would simply let out tiny bursts of nitrogen to produce thrust. As the nitrogen was released from the tank, it would expand and shoot out through the nozzle of the thruster, producing a small amount of thrust and moving the astronaut. This is essentially the same system used on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket, where a series of cold gas nitrogen thrusters are used to orient the rocket as it comes in for a landing.

In order for these cold gas thrusters to work, the nitrogen needs to be stored at incredibly high pressures. In the jetpack, the nitrogen was stored at 4,500psi, around 300 times the pressure of the air we breathe here on Earth. But these thrusters had one drawback. As the gas was used up, the pressure in the tanks would decrease, gradually reducing the thrust with each firing.

The jetpack featured two joystick controllers on each arm. The one on the left would control the up-down, left-right, forward and backward movements. The one on the right would control the rotational movement of yaw, pitch and roll. With this, the astronauts could accelerate at a rate of 0.1m/s2, giving them really precise control over their movements.

Powering the wireless jetpack

The jetpack also featured two batteries which would provide electricity to things like the control systems, cameras and lights. One of the key design features of the jetpack was having two of everything, making it far more redundant. If one gas tank failed, the other one would be there to bring the astronaut back safely. When doing a spacewalk, the jet packs had enough propellant and battery life to last up to 6 hours.

But thanks to the jetpack’s genius design, it was able to be recharged and refilled very quickly by another crew member, allowing the spacewalk to be continued for another 6 hours. So, the jetpack seemed like an amazing new tool for the astronauts to have.

The disastrous test flight

But on the very first test flight, things didn’t go to plan. The astronauts who would be testing the jetpack were Bruce McCandless and Robert Stewart. This was to be a very simple spacewalk, to test out the jetpack’s functionality. But the problems started for Robert before he even left the Space Shuttle. While in the air-lock, Robert followed the normal procedure of yawning to equalize the pressure between his ears and the atmosphere in his spacesuit.

But in doing so, the chin strap on his communications cap broke and sent his microphone and headphones floating up to his head. He didn’t want mission control to know about this problem in case they cancelled the spacewalk. So, he talked it over with Bruce and the crew inside the Space Shuttle and decided to go for it.

In order to hold his communication cap in place, he pushed the back of his head against his helmet and kept it there. With his microphone now halfway up his face, Robert had to shout at the top of his voice every time he communicated with mission control. All of this shouting, paired with the dry pure oxygen atmosphere inside his helmet, made his throat incredibly sore. But if he dipped his chin to reach his drink straw, his headset would come loose, making communication almost impossible.

Despite this, he continued on with the space walk, testing the jetpack and flying almost 100 meters away from the Space Shuttle. This is when he discovered his next problem. The sublimator in his spacesuit which chilled the cooling water became blocked with ice. Following his safety checklist, he turned the temperature control to cold, which spread more water around his suit, using the body temperature to melt the ice.

This immediately made it feel like he had just jumped into the Atlantic Ocean, so he quickly turned it back up to the normal temperature. Now out of ideas, he turned off the spacesuit fan and water pump, hoping that the ice would turn from a solid straight into a gas and disappear into the vacuum of space. All this did though was cause the carbon dioxide levels in his helmet to rise, causing his breathing to deepen, forcing him to turn the fan back on. Robert dealt with several ice blockages throughout his space walk before finally coming back to the Space Shuttle and ending the spacewalk.

Despite this being one of the toughest space walks in the history of spaceflight, Robert went out 2 days later to perform another one using the jetpack. With a bit of tape to secure his communications cap, he experienced a flawless flight. Many astronauts that used the jetpack on future missions found it to be a dream to fly. The level of control it offered astronauts was incredible, but sadly, it wasn’t used for much longer.

The end of the jetpack

At the end of 1984, the jetpack was used for the final time. Following the Challenger disaster, many parts of the Shuttle program had to be redesigned for safety, the jetpack was considered to be an unnecessary risk. As the Shuttle itself continued to develop, spacewalks became easier with the aid of the Shuttle’s giant manipulator arm, which could be used to retrieve faulty satellites.

And with NASA putting more training into tethered spacewalks, the need for the jetpack had disappeared. But its legacy lives on. Now, astronauts wear a slimmed down version of the jetpack called ‘safer’. This smaller jetpack is essentially the astronaut’s life jacket. If an astronaut ever found themselves floating off into space, they could use this jetpack for a short period of time to help them get back to the space station.

Thankfully, this has never happened. And although the jetpack never lived out its full potential as a flying machine, it’s amazing to see how things like this could make a return in the future when we have more and more people in space. The three jetpacks that were made are now in museums across the USA.

Thanks for sharing. I read many of your blog posts, cool, your blog is very good.