This is the Space Shuttle, lifting off on what was about to become one of its most dangerous journeys into space. Almost immediately, fuel started leaking out of its right engine – and just 5 seconds later, an electrical supply failed, knocking its engine control computers offline. Unaware of what was really going on beneath them, the Space Shuttle crew spent the next 8 minutes just moments away from a catastrophic failure, when suddenly… they ran out of liquid oxygen.

The Shuttle had experienced two major problems that should have ended the mission – but miraculously, they happened in such a way that actually ended up saving the crew from complete disaster.

We’re going to look at the tiny objects that led to these huge problems and how sheer luck and miraculous circumstances ended up saving the Space Shuttle.

STS-93’s heavy payload

In order to understand why this flight was so dangerous in the first place, we need to look inside the Shuttle’s payload bay. It was carrying the Chandra Observatory Telescope which, weighing 23 tonnes, was the largest and heaviest thing Shuttle ever launched. It was so big in fact, that there was only one Shuttle capable of carrying it, Columbia. The problem was, Columbia was also the oldest and heaviest of the Space Shuttles, and so this combination put the mission over the Shuttle’s weight limit.

It had to shave off several tonnes before the flight, and so the crew was limited to 5 people, a lighter external tank was used, and all 3 main engines were swapped out for lighter ones. One of these was engine 2019, which had already flown on 18 missions, making it one of the most used Space Shuttle engines.

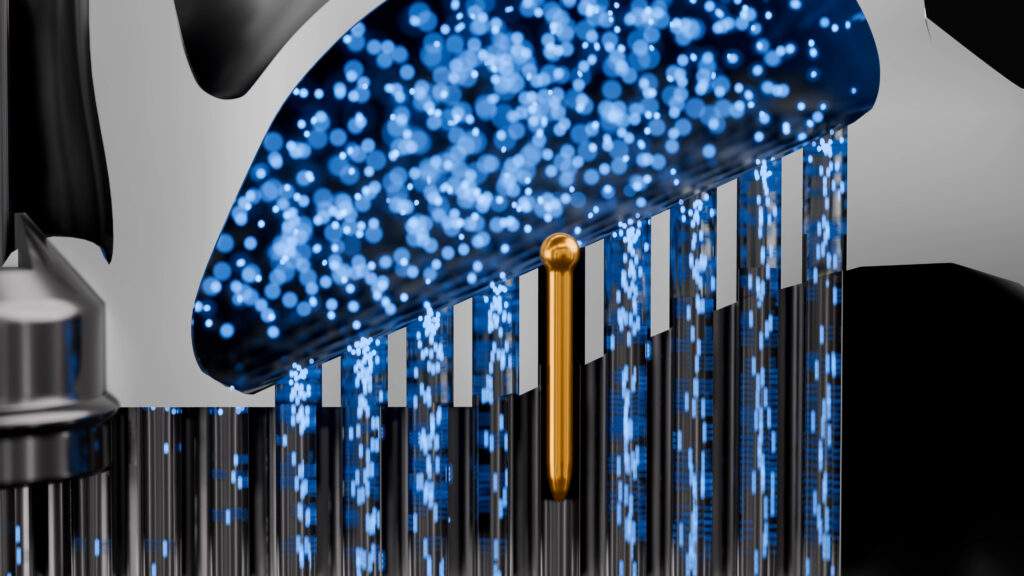

Space Shuttle’s LOX posts

Over time, cracks had started to show in a couple of its liquid oxygen posts. These are the thin pipes that carry liquid oxygen into the combustion chamber. If one of these failed mid-flight, it would rip the engine apart and destroy the entire vehicle.

Instead of replacing these, NASA simply deactivated them by placing a small metal pin at the top, which stopped the liquid oxygen from flowing through. This was common practice for NASA, and it saved the engine from going through a lengthy refurbishment. But as Space Shuttle Columbia ignited its engines, one of these metal pins worked its way loose and shot itself into the combustion chamber at over 30 meters per second.

A golden bullet

In the blink of an eye, it bounced off the chamber walls and punctured a hole in the delicate engine nozzle. This part of the engine is made up of over 1,000 thin tubes, which circulate the ultra cold liquid hydrogen to stop the nozzle from melting. From there, the hydrogen makes its way into the combustion chamber, where it ignites, and produces thrust. When the pin collided with the nozzle, it ripped a hole in three of the pipes, and liquid hydrogen began pouring out of the engine. If just two more of these pipes had been damaged, the nozzle would have melted, causing a chain reaction that would have completely destroyed the vehicle.

The Space Shuttle was just barely hanging on, but all of this went completely unnoticed, since none of the sensors could detect the leak. What the sensors did detect was a lower chamber pressure, since less hydrogen was making its way into the combustion chamber.

In order to fix this, the onboard computers automatically started pumping more liquid oxygen into the engine, which brought the pressure back up to the correct amount. This meant that the Shuttle was now burning through its liquid oxygen too quickly – and if it continued like this, it would run out way before reaching orbit.

But while all of this was going on, a completely unrelated electrical problem had occurred in the vehicle.

Electrical problem

Inside the payload bay were a series of electrical wires that carried power to instruments all over the vehicle. One of these wires ran alongside a small screw that had been over tightened and had a very sharp edge. Over the course of many flights, this wire had rubbed against the screw, and its insulation had been slowly worn away. 5 seconds into the flight, the exposed wire arced onto the screw, causing a short circuit and setting a number of instruments offline.

This immediately set off all kinds of warnings inside the cockpit, one of which was a fuel cell warning. The fuel cells onboard Shuttle used hydrogen and oxygen to produce all of the electricity for the vehicle. If one of these went wrong, the result would be catastrophic. Luckily, this was just a faulty reading, and there was nothing wrong with the fuel cells. The real problem was lurking down below.

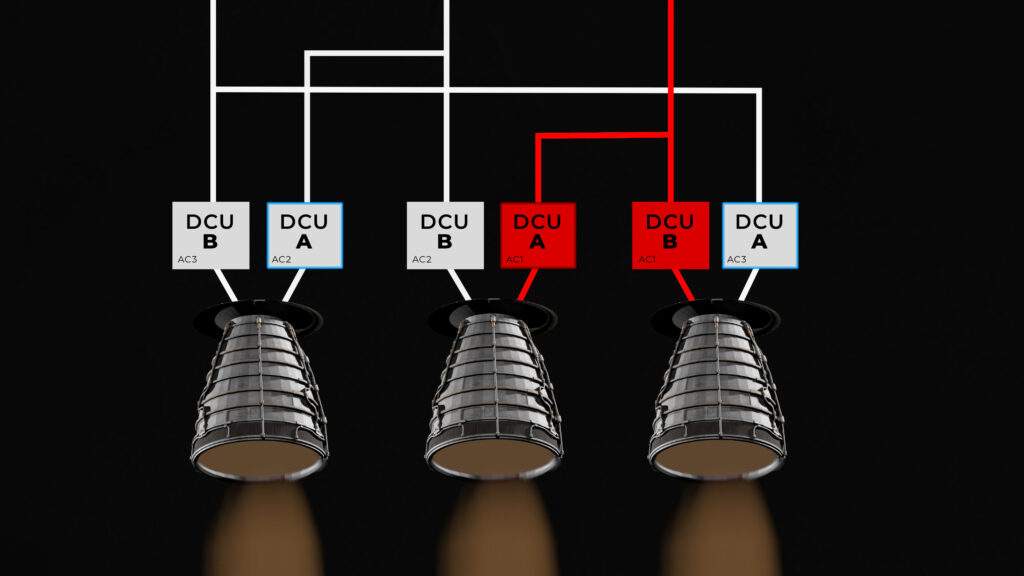

Space Shuttle engine control computers

Two computers in charge of controlling the Shuttle’s engines had been knocked offline, thanks to the electricity shortage. Each engine had a main computer and a backup computer, which would take over if something went wrong. The right engine, which was leaking fuel, had just lost its backup computer, and the center engine lost its main computer. This caused a unique problem that actually turned into a solution.

You see, under normal circumstances, both computers run simultaneously. The data from both computers is compared and averaged out, and this is what is used to control the engines. This means that if a sensor on one of the computers is reading abnormally high or low, it won’t have such a big effect on the engine. As it turned out, the pressure sensor on the backup computer was reading incorrectly, and it was sending back an abnormally high pressure reading. Since the main computer wasn’t there to cancel this out, it tricked the engine into thinking the pressure was too high.

Because of this, the engine started pumping less liquid oxygen into the engine to reduce the pressure.

This now meant that although the right engine was guzzling through too much oxygen, the center engine was using less than normal, and so the problems canceled each other out. If the center engine didn’t have a faulty sensor, or if the electrical supply hadn’t failed, the whole Shuttle would have run out of liquid oxygen much sooner, and it wouldn’t have reached orbit. Had this actually happened, the crew would have had to make an aborted landing back on Earth, still carrying the enormous telescope on their backs.

By sheer coincidence, two completely separate problems occurred that perfectly canceled each other out, allowing Shuttle to reach orbit just 5 meters per second off its desired speed. In the end, the Shuttle was able to make up for this by using its OMS engines, and the Chandra telescope was successfully deployed. Since its main engines weren’t needed for the rest of the mission, the Shuttle and its crew safely made it back to Earth without any issues. After this flight, NASA made changes to their refurbishment policy and damaged lox posts now had to be completely replaced.

Resources

- https://www.scribd.com/document/52892524/STS-93-Space-Shuttle-Mission-Report

- https://waynehale.wordpress.com/2014/10/26/sts-93-we-dont-need-any-more-of-those/

- https://thespaceabove.us/episodes/ep183_sts-93/

- https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/19990100638/downloads/19990100638.pdf

- http://www.collectspace.com/ubb/Forum30/HTML/000409.html

- https://www.nasa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/sts-093-press-kit.pdf?emrc=93f7a4

- https://www.americaspace.com/2014/07/26/making-superman-jealous-15-years-since-the-first-female-shuttle-commander-part-1/

amazing. great animation.

Very good explanation of the sequence of events, so well that I understood them. However, it appears that the author changed liquid oxygen to liquid hydrogen running in the combustion chamber posts. Excessive italics and caps are distracting. But overall, well explained and exciting article!

Great article! I really appreciate the clear and detailed insights you’ve provided on this topic. It’s always refreshing to read content that breaks things down so well, making it easy for readers to grasp even complex ideas. I also found the practical tips you’ve shared to be very helpful. Looking forward to more informative posts like this! Keep up the good work!

It is so amazing that most of the rockets with such huge yet fragile nature launch successfully