It’s a cold rainy night in the walled city of Cordoba, medieval Spain. Watchmen guard the city, unaware that an entire army of christian soldiers are about to launch a surprise attack. In a single night, they conquer the entire city, bringing the muslim rule to an end.

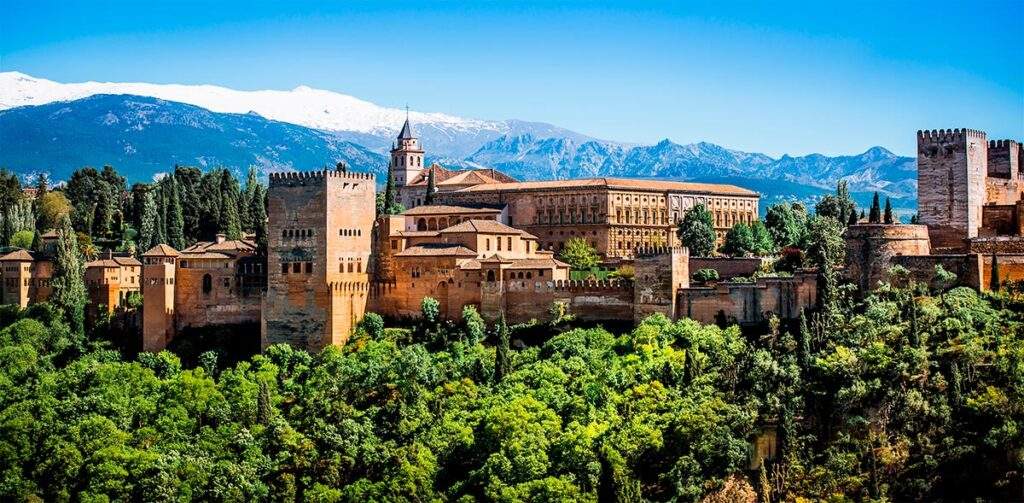

All over the land, muslim cities were being conquered and taken over by the christians. But amidst all of this, one city remained unconquered, Granada.

Thanks to its strategic position and the enormous Alhambra Palace, the city was protected, and it remained untouched for another 200 years.

To this day, the Alhambra Palace still stands as one of the most beautiful pieces of architecture ever made. But as you walk through the luxurious courtyards and hallways, you start to notice something even more special, the water.

Winding its way through the Alhambra is a mind-blowing network of medieval pipes and channels that carry water to vibrant gardens, thermal baths, and elegant fountains. The engineering required to pull this off was astonishing, and it gave the palace things like underfloor heating, and fountains that could tell the time.

This incredible hydraulic system also kept the palace cool and brought life to the surrounding nature for hundreds of years, and it still works to this day.

Getting water to the Alhambra

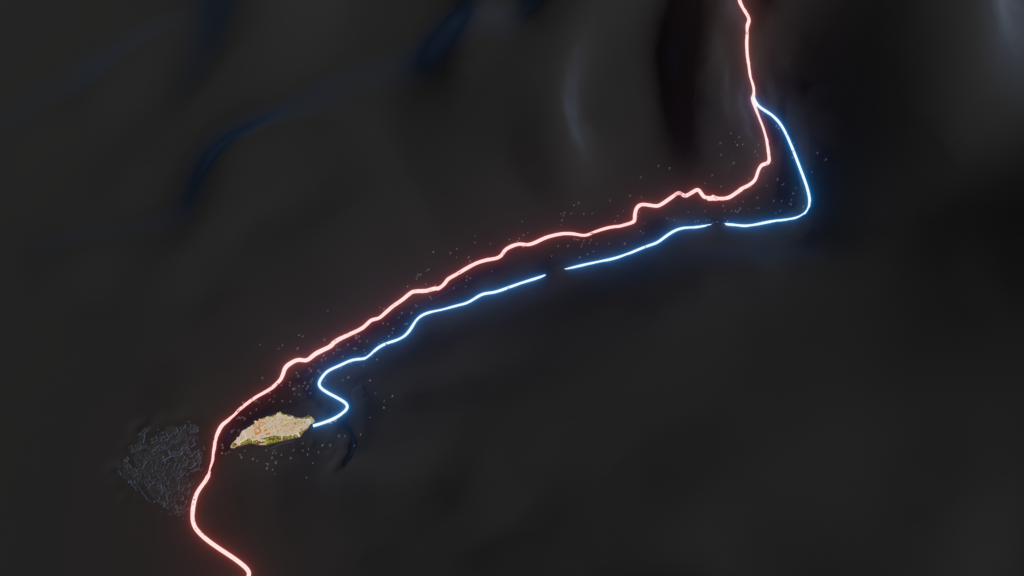

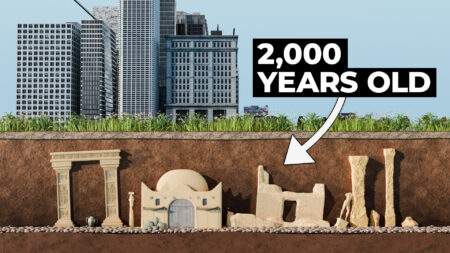

When the ruler of Granada commissioned the palace, the engineers had one major problem. The hill was around 200 meters above Granada’s main river, and getting water up to the palace would be a huge challenge. And so, they followed the river 6 kilometers upstream to a point that was considerably higher than the palace.

From here, they dammed the river and started redirecting it down a new channel known as the Royal Canal. With meticulous planning, it navigated its way through the difficult terrain using tunnels and aqueducts, maintaining a very shallow slope, until it arrived just outside the palace. It was a huge amount of work, and provided the palace with a constant supply of water – but this was only the beginning.

The designers of the palace had big ideas; elegant fountains shooting out jets of water, bathing rooms with showers and underfloor heating, and clocks that were powered by water. All of this required much higher water pressure than the Royal Canal provided.

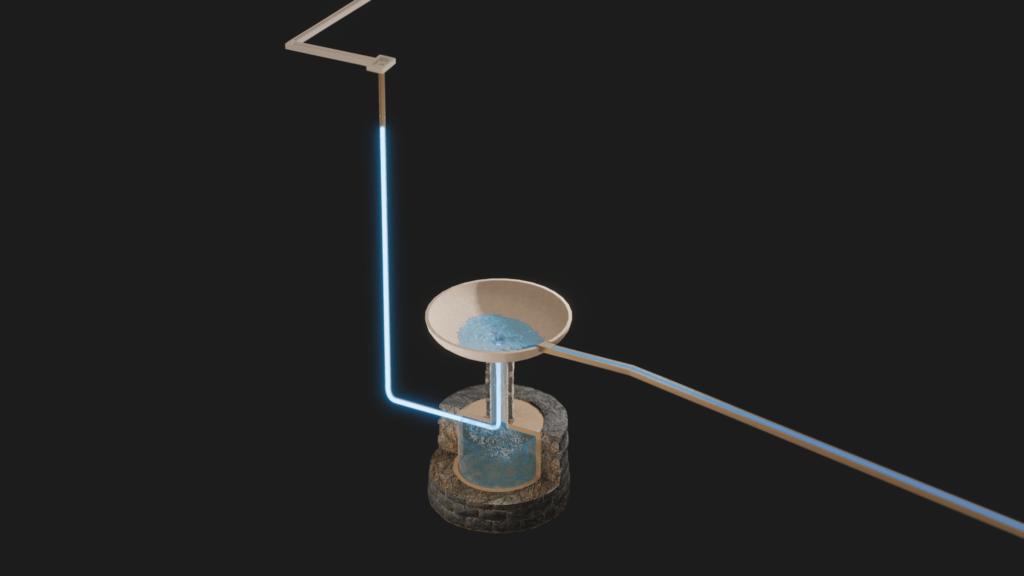

Pressurizing the water system

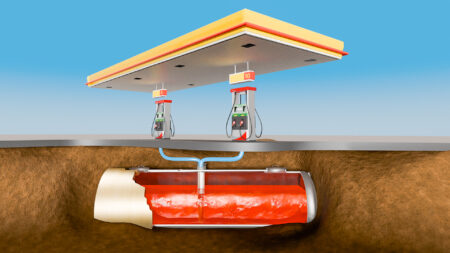

And so, to get around this, the engineers started digging out a large pool in an area much higher than the Alhambra. Below this, the water from the Royal Canal would flow into an underground pipe and collect in a well 60 meters below the pool. At the top of the well, the engineers installed a waterwheel, equipped with buckets that could be turned by an animal.

This would raise the water up to the surface and fill the storage pool with around 400 cubic meters of water. Having all of this water stored above the palace pressurized the entire system, and at the same time, gave the palace a backup supply of water in times of drought.

From here, the water passed over an aqueduct and into the palace, where things start to get really interesting.

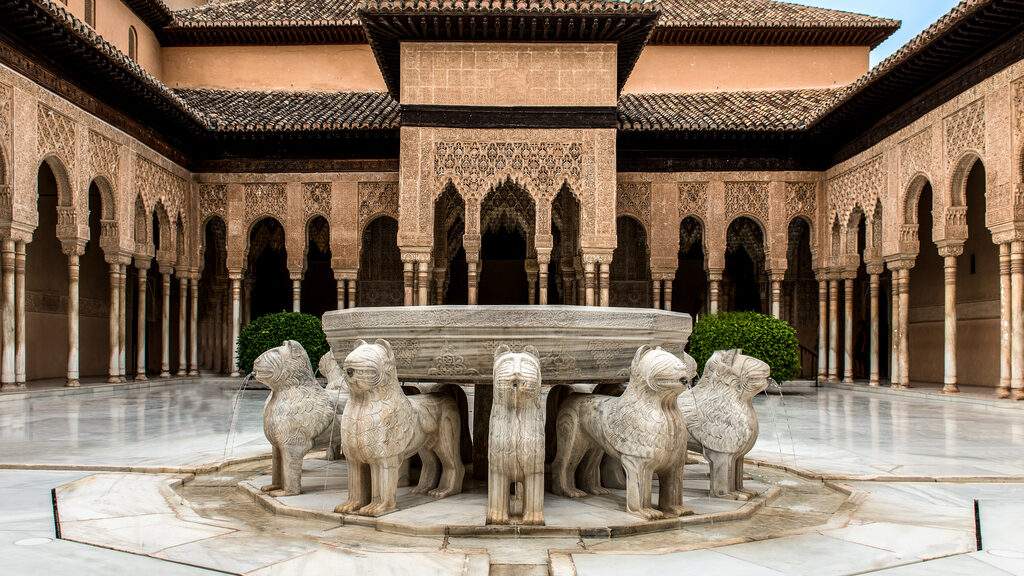

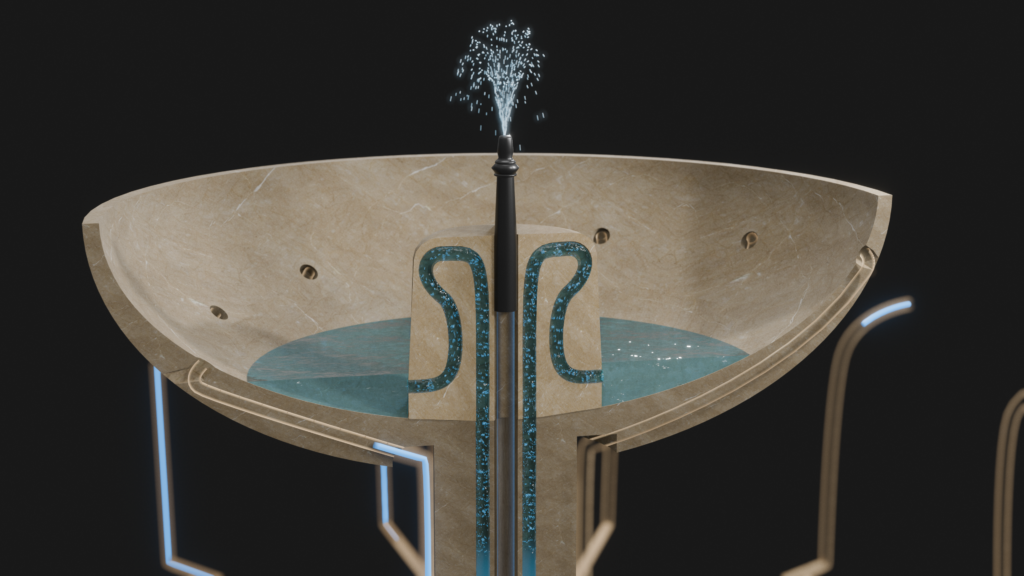

Court of the Lions Fountain

The water would split off into a complex network of carefully designed channels, carrying just the right amount of water to the pools and fountains all around the palace – the most impressive of which was located at the heart of the palace. Built in the 14th century, it featured 12 lions that each shot out a jet of water to show what time of day it was.

In a controlled sequence, the lions would activate hour by hour, until all of them were spouting out water by midday. The system would then reset itself and the process would start again.

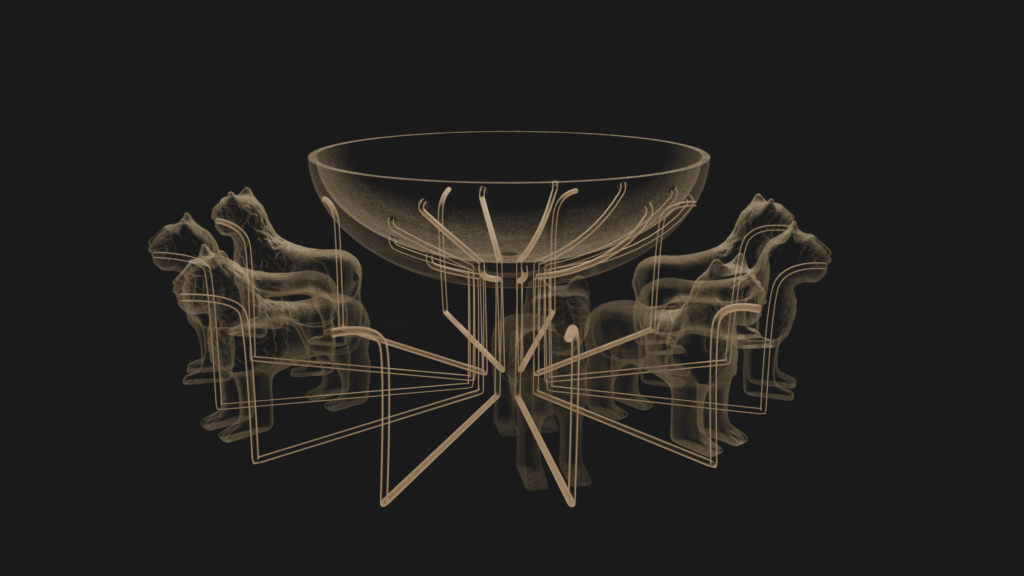

But how was this possible with medieval technology? The large bowl at the center of the fountain had 12 holes placed at very specific heights, each leading to a lion via a series of internal pipes.

These holes were carefully calculated to contain the exact same volume between all of them. A central pipe would fill the bowl at a slow and constant rate, causing the water level to rise and activate the lions one by one. The holes were so precisely calculated and the water supply was so constant that it would take exactly one hour to reach the next hole.

After 12 hours, the bowl would be full of water and a clever siphon inside the bowl would reset the system naturally. As the water inside the bowl started to rise, so did the water in the siphon. Once it reached the top of the siphon, it would curve and start falling down the drainage pipe.

Siphon device

At this point, a seal was created and no air could get in to replace the falling water. This activated the siphon and the surface tension of the falling water would pull the rest of the water with it. In a matter of seconds, the bowl would drain completely and the process would start again.

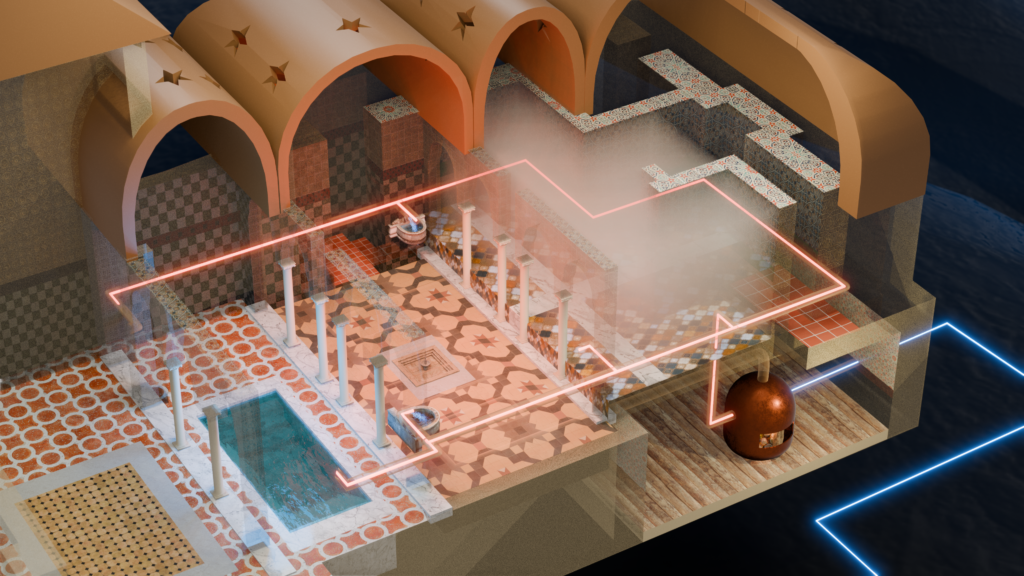

The water from the lions would exit via 4 shallow channels in the ground and continue on throughout the palace, eventually reaching another engineering marvel, the thermal baths. This is where the kings and diplomats would come to relax and make deals. It featured a cold plunge pool, a hot room with heated flooring and a steam room.

Thermal baths

The water would enter a control room underground and pass through a copper boiler that was heated by burning wood. From here, the hot water would flow through pipes to various fountains and showers around the baths. To provide under floor heating in the hot room, the steam from the boiler was directed through channels underneath the marble floor.

From there, the steam would travel up through pillars in the steam room and exit through small vents, filling the room with water vapor. The roof had a series of star shaped windows that could be opened and closed to control the level of steam.

As the water continued on through the Alhambra’s network of fountains, channels and pools it had another benefit, cooling. Granada is an extremely hot part of Spain, but as the warm air blew over the pools and fountains, the water would evaporate, cooling the air surrounding the palace and making it a very comfortable place to be.

Making water travel uphill

The water continued all the way through the Alhambra until it reached the western portion of the palace, where the soldiers lived. It was built slightly higher than the rest of the palace and so the water had to make a final 6 meter climb to reach it. We saw how waterwheels were used to raise water, but for this section, they came up with something much more impressive.

(Paper that explains this device in more detail pg. 370)

This was a special device that didn’t require waterwheels, animals or any external power, here’s how it worked.

Water from the system would flow into a container with a hole in the bottom leading down to another container below. As the water traveled down the pipe, a whirlpool would form in the top container. At the center of the whirlpool, a low pressure area would form, sucking air downwards and into the container below. Here, the air and water would mix and this gassy water would be forced into a thin pipe.

The potential energy in both pipes was the same, meaning under normal circumstances, the water pushing down in this pipe would push the water upwards equally in this pipe. But since the water in the thinner pipe was full of air bubbles, it was lighter and could travel higher up the pipe.

Although it may seem like this is cheating physics by somehow gaining energy, it’s important to note that only a small percentage of the water that enters the whirpool makes its way up the thinner pipe. The rest of the water exits the 2nd container via a hole on the bottom. This is the basic principle of an air-lift pump, a modern device where compresed air is inserted into water.

By passing a constant flow of water through the whirlpool, this device was able to raise water 6 meters higher than when it entered, providing water to the rest of the palace.

Today, many of the clever water systems around the Alhambra still work, and it’s all thanks to the incredible engineers who made them hundreds of years ago.

Family grew up near there, visited many times, wish I knew this before I went! Clearly the Lion Fountain Clock is my favorite, even without the Oprah browser making it work!

Hi there – I’m having a really hard time finding sources for the last part about the 6 metre rise using a whirlpool to aerate the water. This idea is fascinating, but I’ve looked through your references and am not seeing it mentioned. One has to wonder if water pressure alone wasn’t the way the water was raised, as the palace had ample pressure to create a lift of 6 meters in one piping system. However, this idea of a funnel aerating the water is so intriguing I just want to find one other source that talks about it so that I can learn more and conduct my own experiments at home. There have been a few people online asking about this and we are all anxious to learn more. Are you able to provide a reference to another source that discusses this? I truly hope so.

Your videos are amazing, and I am so thrilled that moving into engineering themes outside of space has seen a well-deserved bump in subscriptions and viewers! Your teams’s modelling work is great.

Hey, I happen to be digging into this at the same time as you. Found this, page 371 has a diagram and 370 has an explanation: https://sci-hub.se/10.1093/jis/etw016

Yeah that is the best source I found

Ah! Thank you so much! I had all the references open but I somehow missed this one (it was very late). I appreciate you drawing my attention to it. It is certainly a fascinating concept. I don’t immediately see why a discharge valve would have been needed (F, in the diagram) so I guess I’ll have to make a prototype. Thanks to all for drawing my attention to this.

Hey Sean, thanks for the kind words! The best source I found for this was a paper called “The Mastery in Hydraulic Techniques for Water Supply at the Alhambra”. I found it here and I was able to get a free trial to read it, check it out if you can. https://www.deepdyve.com/lp/oxford-university-press/the-mastery-in-hydraulic-techniques-for-water-supply-at-the-alhambra-glnye9pQy1?articleList=%2Fsearch%3Fquery%3DThe%2BMastery%2Bin%2BHydraulic%2BTechniques

Oh that’s great – thank you Ewan. I’m very excited that this device has been studied and thankful for your video for bringing it to my attention. My family looks forward to your next videos!

The quality of these articles/videos is impressive. So much great information, thank you for the great work!

good

I’m genuinely impressed by how in-depth this post is. The research and thought you’ve put into it are evident, and I appreciate the way you’ve presented the information in such a clear and accessible manner. This is a post I’ll be coming back to regularly.

Thanks Tessa! I’m glad that you found it interesting too.

Nice

Thanks I have just been looking for information about this subject for a long time and yours is the best Ive discovered till now However what in regards to the bottom line Are you certain in regards to the supply

The water raising device diagram is missing the drain since most of the water is drained.

thank you ewan cunningham

Hi. I’ve seen the youtube video of this article. Where, in your sources, have you seen the fountain of the lions being a clock with such a mechanism? Thanks

How is the water and air mixture forced into the smaller pipe?