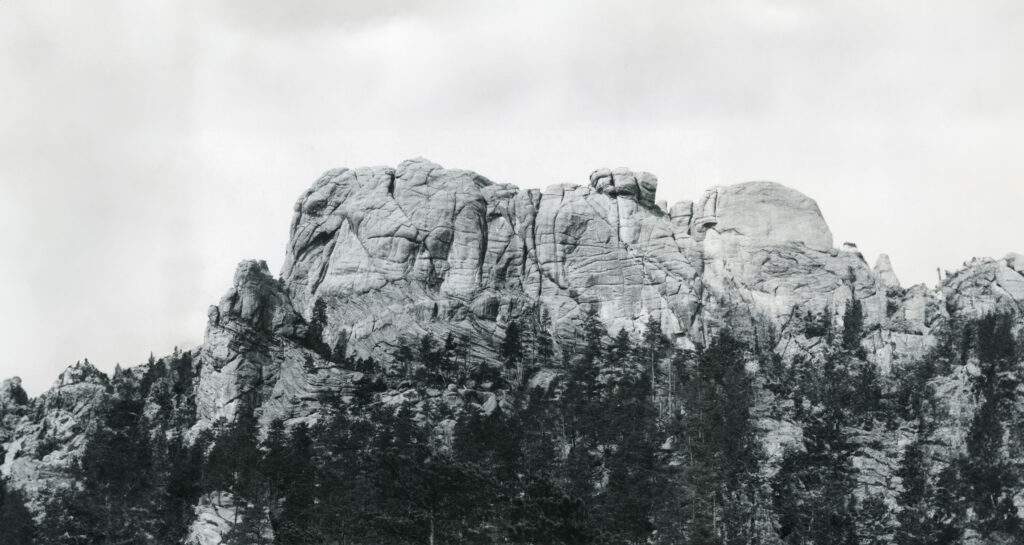

There is something unusual about Mount Rushmore. Unlike most sculptures which look painstakingly crafted, Mount Rushmore almost seems like it formed out of the mountain naturally, and not by the work of a great sculptor. The reality is, Mount Rushmore is not only a work of art, but an engineering masterpiece.

Despite having zero artistic experience, an enormous team of gold miners managed to bring these giant heads into existence, using jackhammers, dynamite and some clever engineering. We modeled the entire thing, to show you how they mapped the design onto the mountain using ancient Greek technology, and how all of this was done without losing a single man. But in order to understand why Mount Rushmore exists in the first place, we need to go back in time.

Why Mount Rushmore?

In the early 1920’s, the state of South Dakota was just a few decades old – and with very little to offer, it was struggling to get its foot in the door. State historian Doane Robinson saw how tourists from all over the country had been flocking to a new sculpture in the state of Georgia, and this gave him an idea. He thought that a much larger and more elaborate sculpture in the black mountains of Dakota could bring in even more tourism and crucially, money from other states.

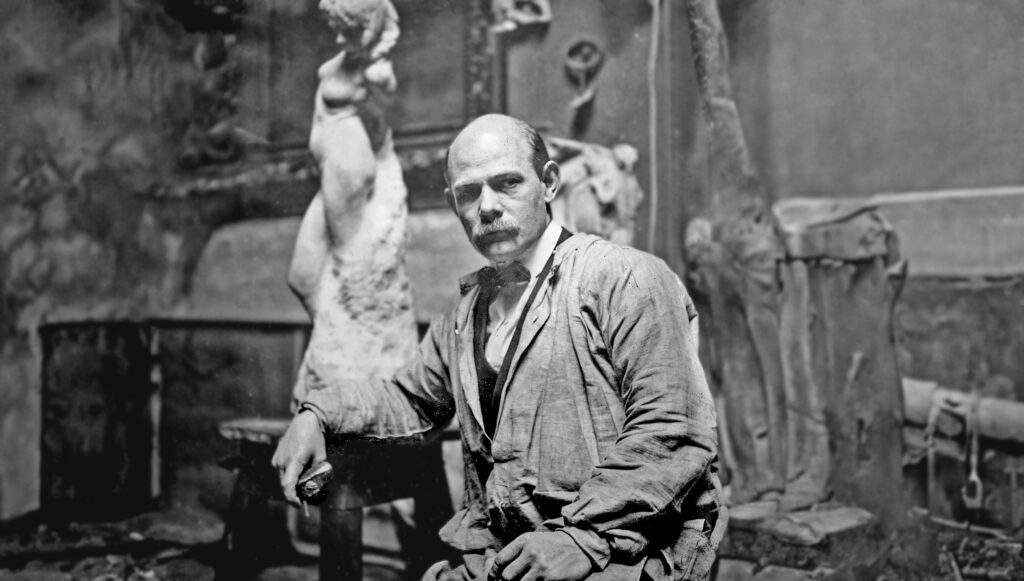

He reached out to the sculptor Gutzon Borglum, and asked if he’d like to make an enormous sculpture of America’s Wild West Heroes. Borglum was excited by the idea, but thought that more national figures like US presidents would draw more attention.

A year later in 1925, Borglum traveled to South Dakota to search the surrounding area of Harney Peak for a mountain or piece of granite that was strong enough to carve a massive figure. A state forester led Borglum on horseback to three different mountains he thought would be appropriate; Old Baldy, Sugarloaf and finally Mount Rushmore.

Borglum fell in love with Mount Rushmore right away. Its 400-foot high wall seemed like the perfect blank canvas, according Borglum. The mountain was composed of Harvey Peak granite, a form of igneous rock common to the Black Hills, which had a mix of quartz, feldspar, and other minerals. With fine grained veins running through the rock, it had a low erosion rate but was quite susceptible to cracking.

After analyzing the Mountain again with Geologists, they confirmed that the granite was very hard and durable. Borglum knew that this would be the perfect blank canvas for his project.

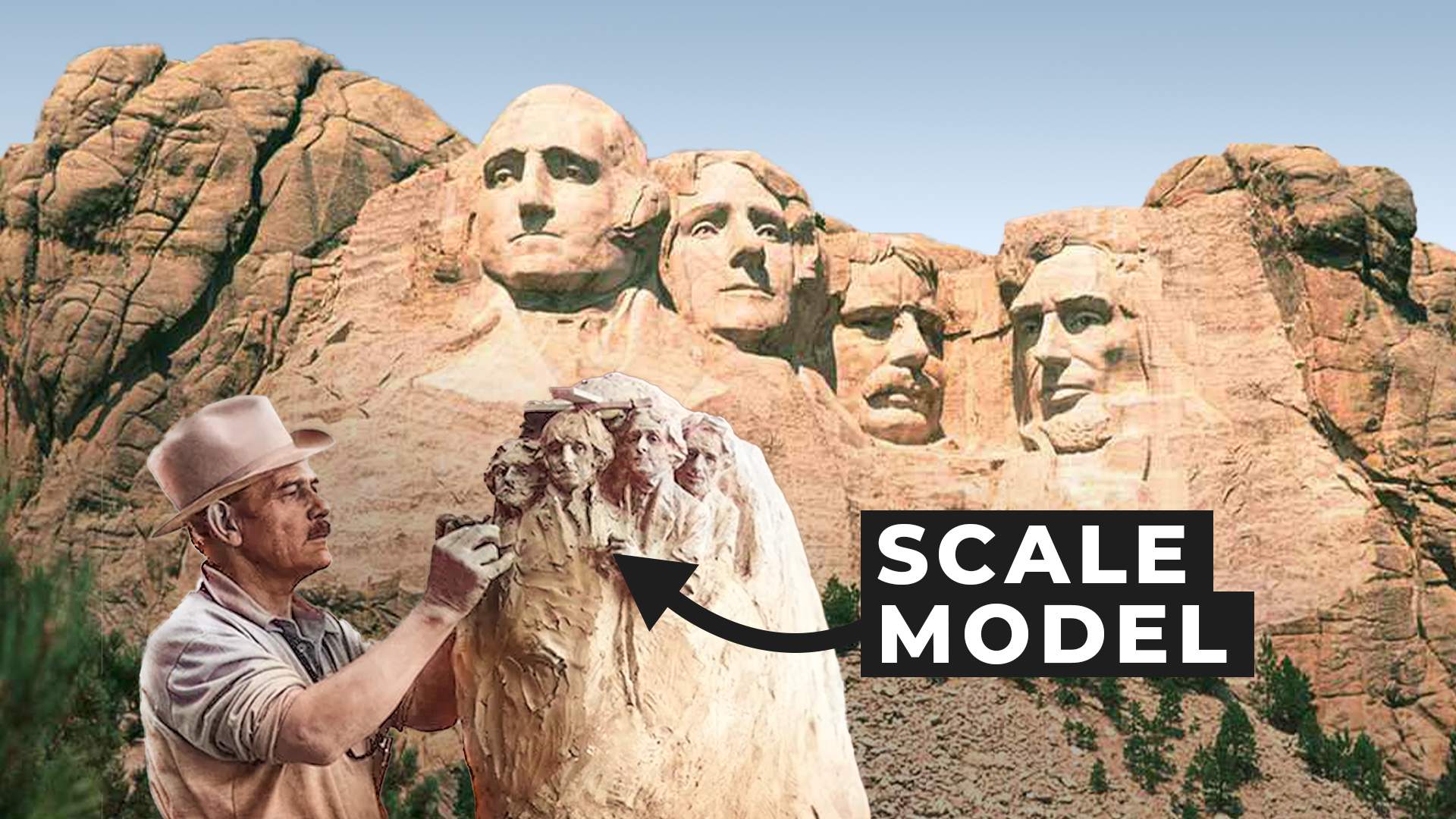

With the mountain secured, he started studying photographs of the presidents, and put together a 1 to 12 scale model. Now, he had to figure out how he was actually going to make the real thing.

Setting up the Mountain

At the time, Mount Rushmore had nothing: no roads, no electricity and no way for workers to even climb the mountain, let alone carve a 60 ft statue. And so, in the summer of 1927, a road was built that could carry goods and people to the site. Soon after, an entire village popped up around the base of the site, with tool shops, blacksmiths and houses for the workers. An enormous staircase was built to the top of the mountain and a cable car was set up to carry tools and materials back and forth.

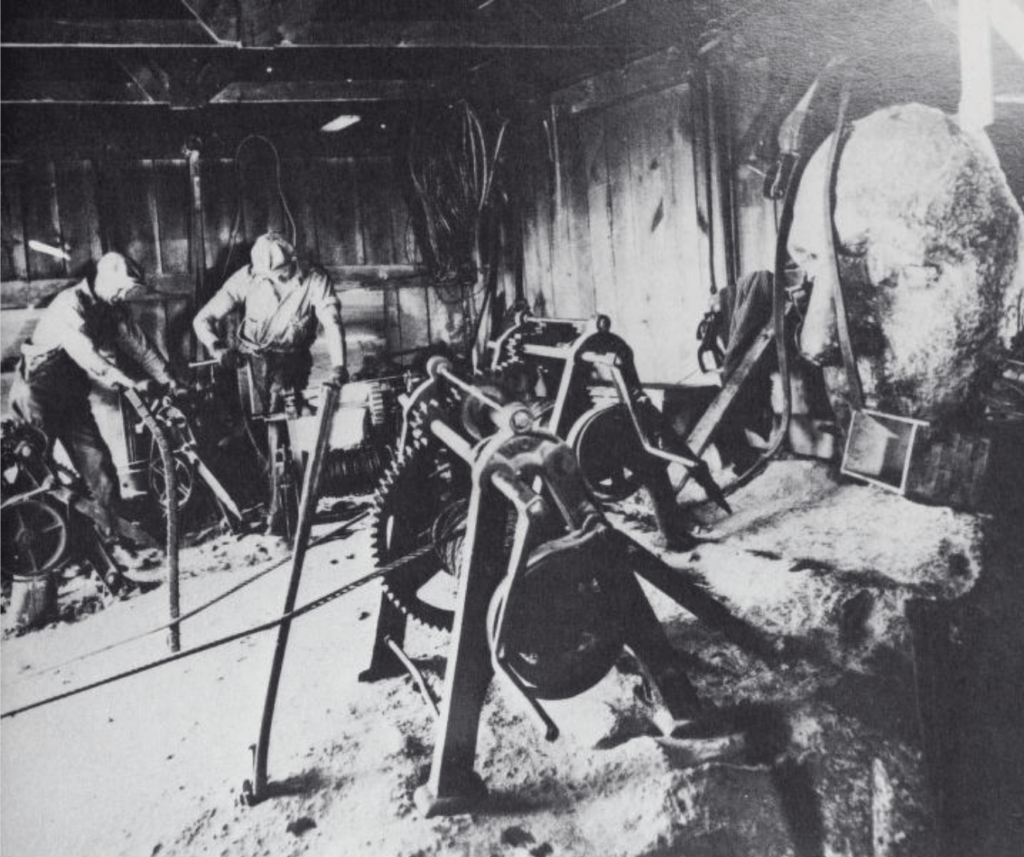

A winch house was also built at the top of the mountain, where operators could raise and lower the brave workers on small seats to any point on the mountain. With all of this in place, the team could finally start carving out the first head of George Washington.

Starting to carve Mount Rushmore

With the help of carefully placed dynamite, the crew started tearing off large chunks of surface rock until they had a rough egg-shaped head. The powdermen who handled the dynamite were so skilled, that only with explosives, they could get to within several inches of the desired shape. From here, it was up to the workers to carve out the face using jackhammers.

But handling these 30 kilogram jackhammers on the side of a cliff would be a huge challenge, and powering them would require more clever engineering. The jackhammers ran on compressed air, and so a building at the base of the mountain was set up to power them. It contained 3 massive air compressors that ran on electricity provided by the local gold mine.

These would run all day, compressing air into a pipe that ran for 2,000 feet, all the way up the side of the staircase and into a building at the top of the mountain. From here, up to 16 jackhammers could be connected at a time.

To stop the jackhammers from jumping all over the rock, they developed their own techniques, sometimes installing chains to grab onto and sometimes using their own feet to guide the jackhammer into the rock. The workers became experts at operating the jackhammers, but without any artistic or sculpting experience, how did they know where to drill?

But during that first year of carving, there were two huge problems threatening to put an end to the project, the weather and lack of money. In September of 1928, it started snowing, much earlier than normal. That winter ended up being extremely harsh and the project had to be called off until the weather improved. The project had just $20 in the bank and owed $20,000.

Borglum and some of his associates went behid the scenes and tried to get $250,000 from the government to help with the project. They agreed to Borglum’s request and set up the Rushmore Bill. But time was running out and they needed president Coolidge to sign the bill. He ended up signing it with just 6 days left in his presidency. Borglum was back in business.

Mapping out the design

On the Stone Mountain memorial, Borglum used a large projector to map out his design. But Mount Rushmore was much larger, and the 3D nature of the faces would make this method impossible. He had to figure out how to transfer the data from his model onto the mountain.

He took inspiration from the Greeks, who were able to make identical copies of Roman statues using a pointing machine. This was a tool that could measure specific points on a sculpture, relative to a reference point. This could then be transferred onto a different sculpture, giving the artist a guide to carve to. By doing this for thousands of points, the exact shape of the sculpture could be replicated.

This worked well for creating replicas of the same size, but in order to scale up his design, Borglum would have to get creative. He came up with his own pointing machine, which was essentially a metal arm with a weighted point at one end that could swing around a fixed axis.

By placing the weighted point somewhere on his model, he could get 3 measurements: the angle of the point, its horizontal distance and its vertical distance. By simply multiplying these 3 measurements by 12, the exact same point could be transferred onto the mountain. But for that, Borglum would need to build a much larger pointing machine on top of Mount Rushmore. And so, that’s exactly what he did.

Using this giant machine, thousands of points could be marked directly onto the mountain, showing the workers where to drill, and exactly how deep they should drill. Borglum himself would often go up to the mountain, hang over the edge and mark these points onto the rock.

Honeycomb drilling technique

Instead of carving out the entire part, the workers would drill a series of holes close together in a honeycomb pattern. Then, using masonry tools, the rock between the holes could be hammered out. After a couple hours of solid drilling, a steel worker would come down on a harness with replacement bits to keep the workers drilling.

The work was tough, and the men spent 8 hours a day dangling over a 500 ft cliff edge for just 50 cents an hour. To earn a bit more money, they developed a side business, selling chunks of this honeycombed rock to tourists, who began showing up at the base of the mountain.

After some negotiating, a tourist might pay up to 6 dollars for the rock, thinking it was a rare stone. Once the tourist had left, the workers would call up to the top of the mountain and ask them to send down another piece of rock.

Over the next few years, work progressed and eventually George Washington’s head was done. The cable car had been strengthened, and so now the workers didn’t need to use the enormous staircase. Borglum had assembled a well oiled team, and so he turned his attention to the finer details.

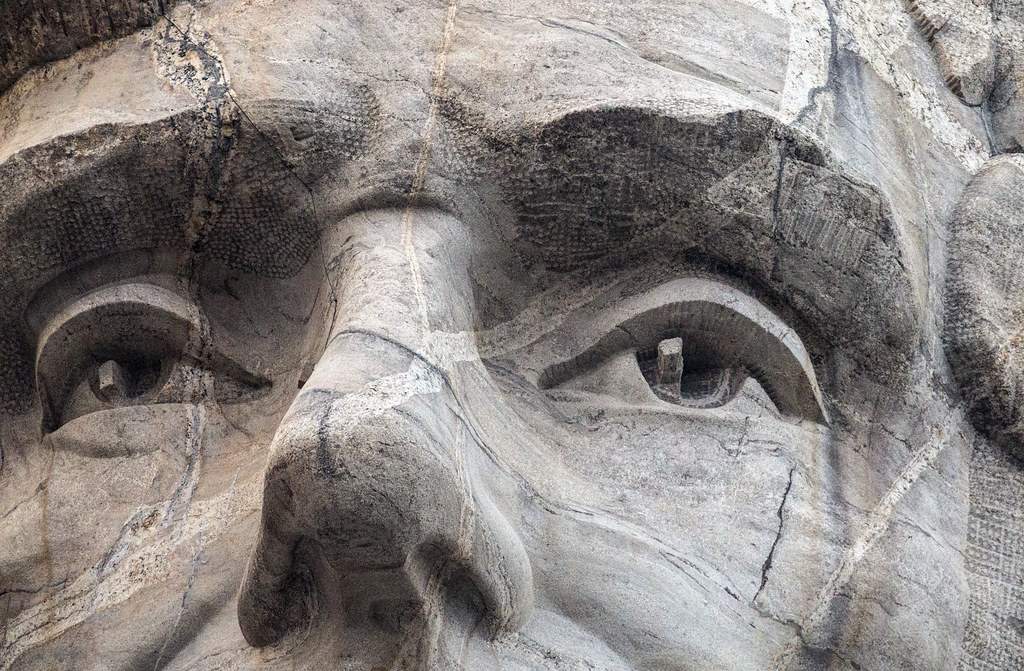

Sculpting the eyes

One of the trickiest parts about the sculpture was the eyes. Typical Greek sculptures have perfectly smooth eyes which look flat and lifeless. To give the eyes a realistic shine, he cut out a hole in each eye that was deep enough to always be in shadow. This gave the eyes their dark look.

Then at the center of the pupil, a square section would be left uncut to give the impression of a reflection in the eye. This was an extremely risky process, since the rock could fall under its own weight at any moment. Its effect was amazing, and when viewed from far away, these square sections gave the eyes a shiny texture.

To finish off the heads, workers would do a process called bumping, which would smoothen out the surface and pulverize it, turning it into a whiter color.

The carving of Mount Rushmore went on for 14 years, but in the end, it was never quite finished. The original plan was to have each president carved down to their waist – and a secret tomb, designed with lavish decorations, had only just been started when the project came to an end.

The secret vault

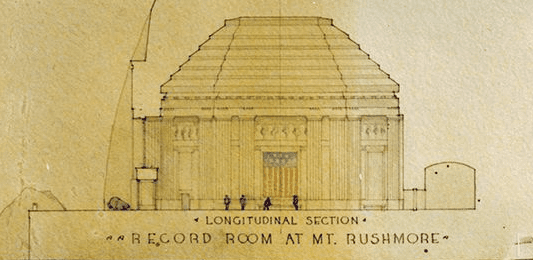

As the heads neared completion, Borglum’s started to think about how future generations would see his work. His idea was to make a vault room that would hold the most important documents from US history. So, in 1938, Borglum and his team began carving out a giant vault room directly behind Mount Rushmore.

His plan was also to build an enormous 800-foot granite stairway to reach the room. The steps would begin near the base of the mountain, next to his studio and gradually rise up to meet the mountain behind Lincoln’s head, leading directly into the entrance of the vault.

Inside the hall, there would be bronze and glass cabinets containing important historical documents, such as the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

The entrance was meant to be 20 feet high by 14 feet wide with cast glass doors opening into a secondary chamber. An enormous bronze eagle, would be placed above the door. Words inscribed over the eagle would read: “America’s Onward March” and “The Hall of Records.”

Work halted in 1939 when Congress directed that construction should be executed only on the faces.

The 2nd World War took away all of the attention and money from Mount Rushmore, and just a couple of years later, Gutzon Borglum passed away. Ultimately, Borglum and Robinson achieved their goal of putting South Dakota on the map. Over 3 million tourists visit these 4 heads every year, and it remains one of the most iconic and recognizable works of art ever created.

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here The sketch is attractive your authored material stylish nonetheless you command get got an impatience over that you wish be delivering the following unwell unquestionably come more formerly again since exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike

certainly like your website but you need to take a look at the spelling on quite a few of your posts Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I find it very troublesome to inform the reality nevertheless I will definitely come back again

obviously like your website but you need to test the spelling on quite a few of your posts Several of them are rife with spelling problems and I to find it very troublesome to inform the reality on the other hand Ill certainly come back again

Your ability to distill complex concepts into digestible nuggets of wisdom is truly remarkable. I always come away from your blog feeling enlightened and inspired. Keep up the phenomenal work!

Hello my loved one I want to say that this post is amazing great written and include almost all significant infos I would like to look extra posts like this

Hello! I just finished reading your post and wanted to say how insightful it is! You highlighted some really important aspects that are often missed. I found the way you presented everything especially relatable and believe this will be incredibly helpful to your readers. On a related note, I’ve been writing about something similar on my website, focusing on [mention related topic]. I’d love to know your thoughts on it! Thanks again for sharing such valuable content. Keep up the excellent work!

I’ve been following your blog for quite some time now, and I’m continually impressed by the quality of your content. Your ability to blend information with entertainment is truly commendable.

how come it says that he came across Mount Rushmore, a 500 ft tall cliff edge made from a fine-grained granite, but then it says that he needed to figure out how transfer his 5 foot model to a 60 foot cliff edge