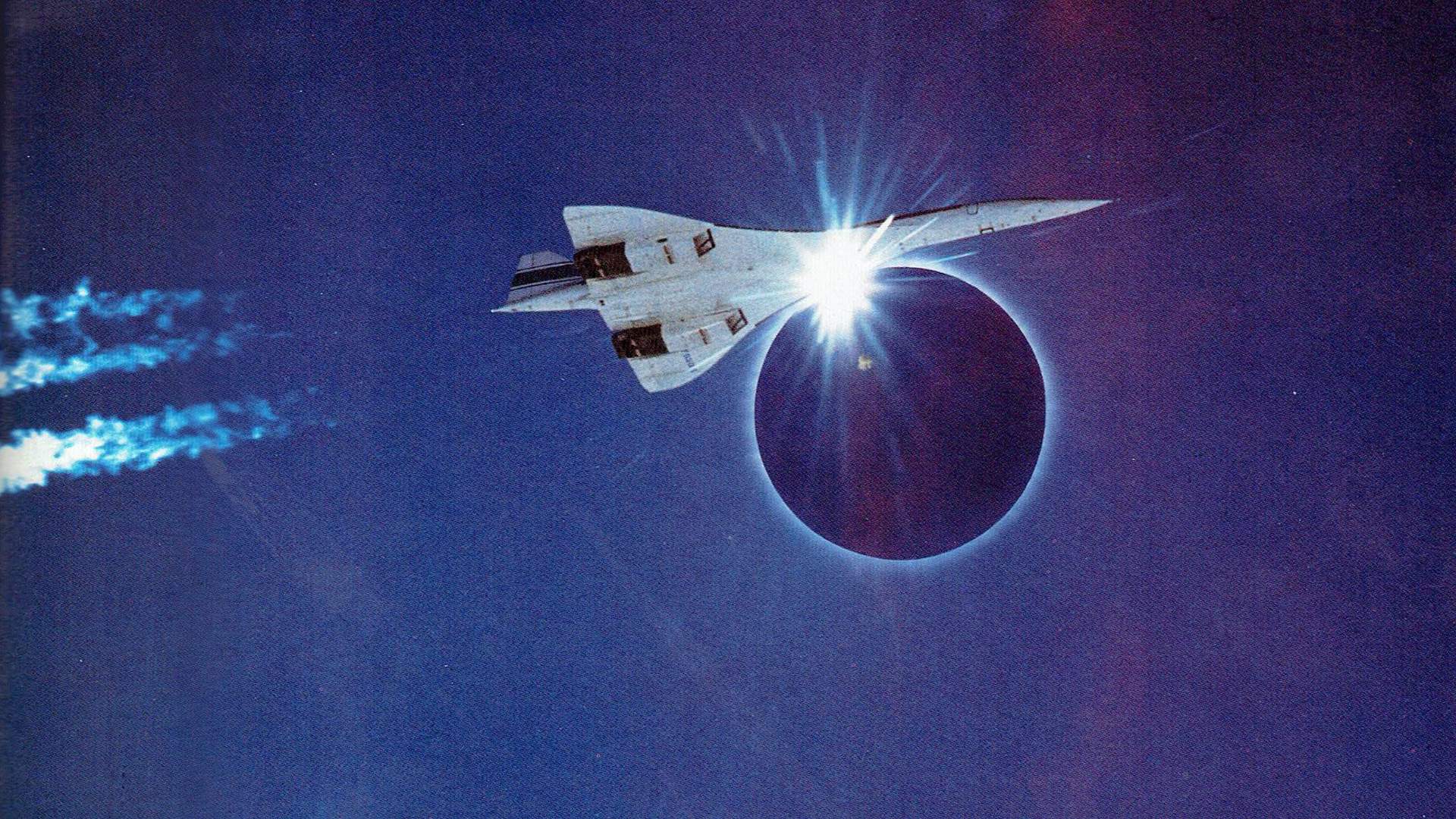

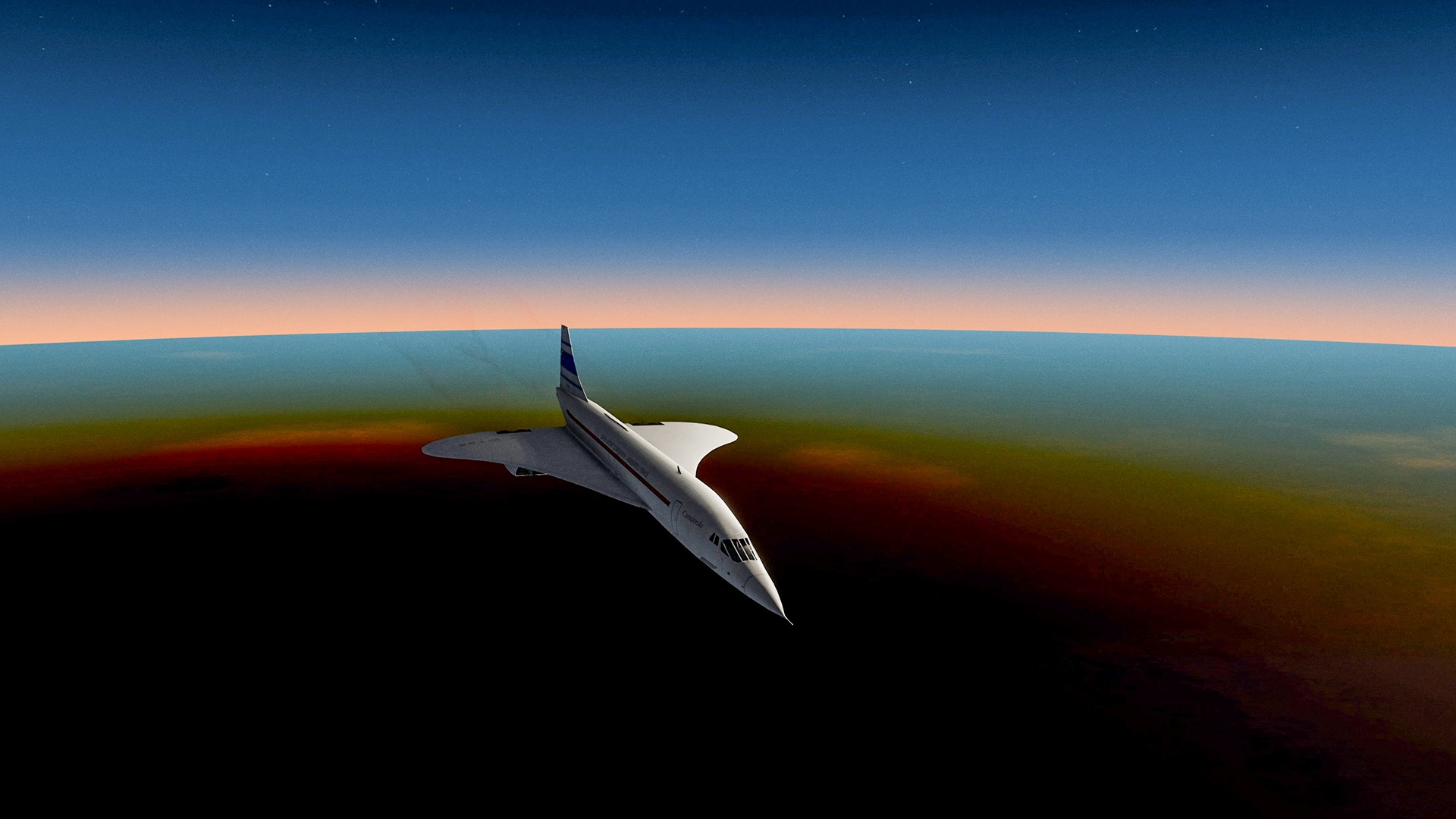

This is Concorde, flying over Africa on a flight like no other. The Sun, which was directly above Concorde, just went completely dark in what was to become the most unique solar eclipse ever witnessed. Total solar eclipses, where the Sun is fully hidden by the Moon, are rare and typically only last for a few minutes.

But in 1973, scientists were able to cheat and experience 74 minutes in the Moon’s shadow by flying in the only vehicle capable of chasing an eclipse. This was an incredible mission that required pinpoint accuracy and timing to intercept the Moon’s shadow as it traveled at over 2,000km/h across the Earth’s surface. We modeled the entire thing to show you what this incredible mission looked like and how a small team of scientists managed to pull it off.

Preparing for the 73 Solar Eclipse

In 1972, French astrophysicist Pierre Lena began preparing for the upcoming eclipse. This was to be one of the longest in history, with a duration of over 7 minutes. An eclipse this long wouldn’t happen for another 200 years, so he was eager to make the most of it.

He was particularly interested in observing the Sun’s corona, the area of hot gas where the temperatures shoot from 5,000 degrees to over 1 million degrees. The corona is usually invisible from Earth – but during an eclipse, the Sun disappears and the corona lights up, giving scientists a rare view into this mysterious cloud of plasma.

But even during an eclipse, studying the corona is difficult, since clouds and the Earth’s atmosphere get in the way. And so for the 1973 eclipse, Pierre wanted to step things up a notch. Although there were faster planes around like the SR-71 – none of them could match the endurance or cabin space of Concorde.

Using Concorde to chase the Eclipse

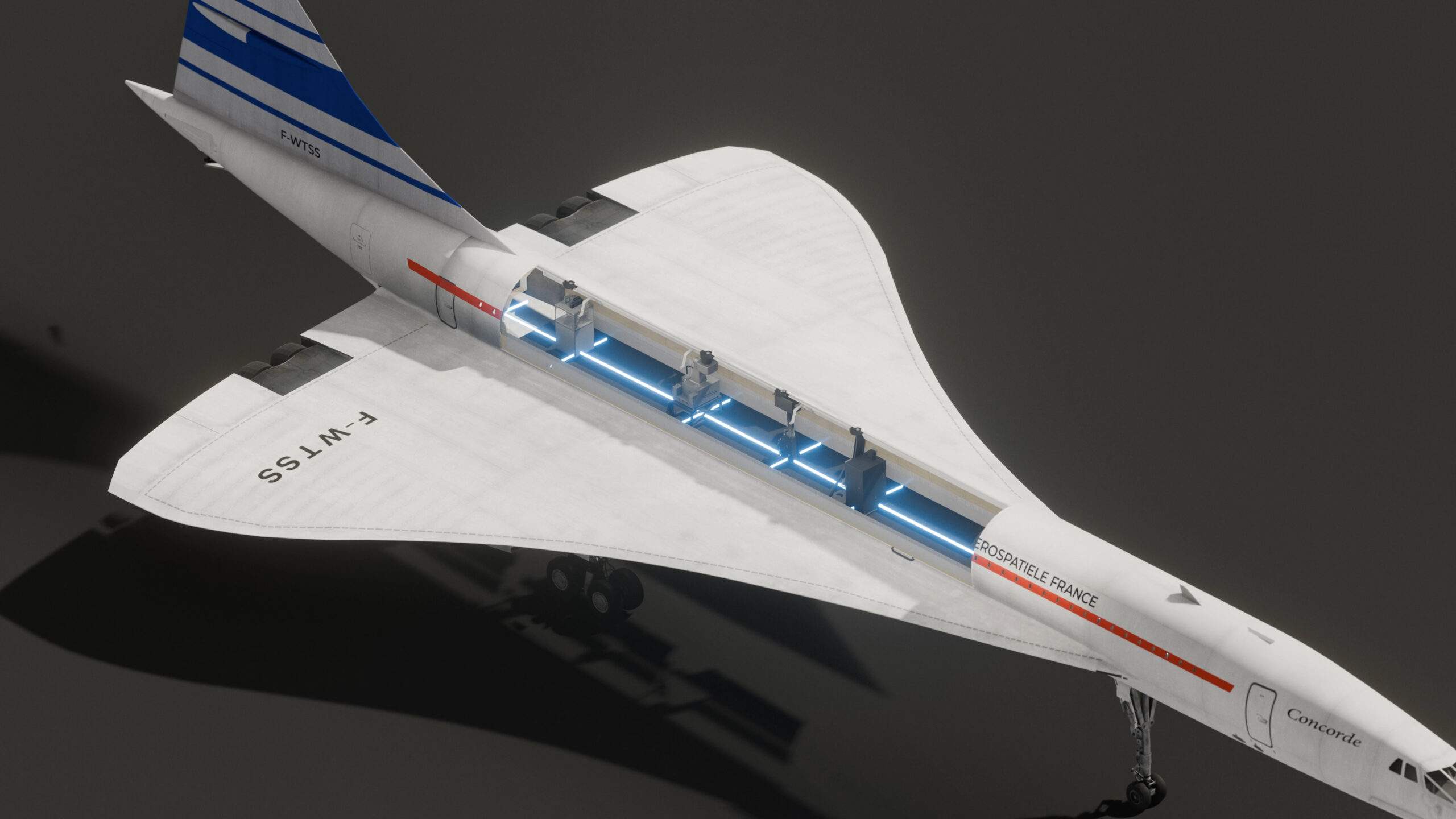

And so Pierre asked legendary Concorde test pilot Andre Turcat if he could use Concorde to chase down the eclipse and fill the plane with science equipment. Concorde was brand new at the time and commercial flights hadn’t even begun yet. Aerospatiele, the French side of Concorde, were excited about the idea and let him use Prototype 001 for the flight, with Turcat piloting the aircraft. Pierre and Turcat got to work, coming up with a flight plan that would maximize their time in the Moon’s shadow. Before we look at how the flight worked, we need to understand the basic principles of solar eclipses.

Eclipses explained

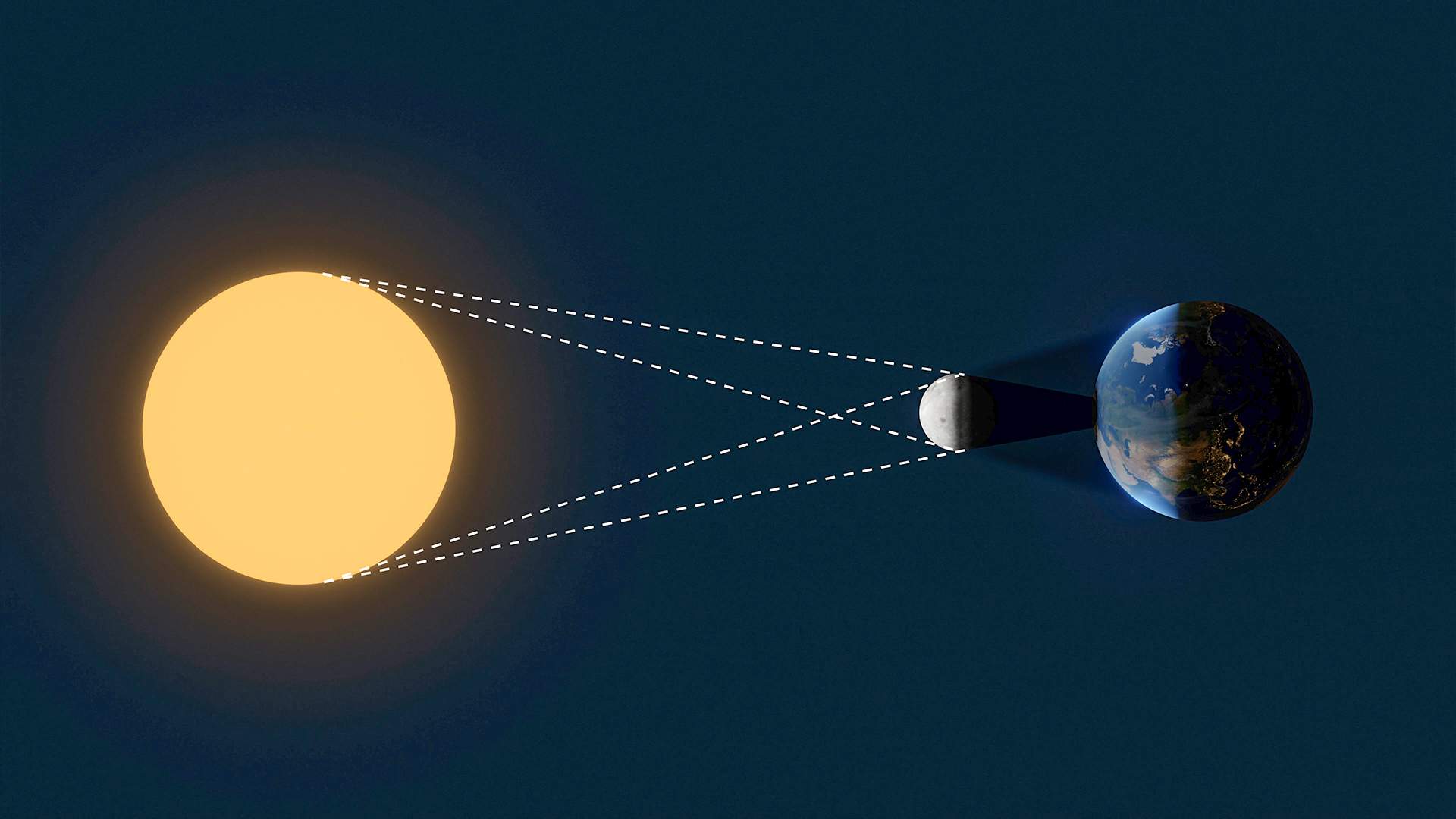

An eclipse happens when the Moon passes in front of our view of the Sun, blocking out its light and casting a large shadow over Earth. Most parts of the shadow will only experience a partial eclipse. But at the very center of the shadow is a much smaller area where the Sun is fully blocked – this is where the total eclipse happens.

As the Moon moves, the shadow also moves across the Earth’s surface, meaning that any point along the path will only experience a few minutes of complete darkness. For the 1973 eclipse, the shadow was set to begin at the edge of South America and work its way over to Africa, where the totality would be at its fullest. It would be moving over the ground at around 2,200km/h, slightly faster than Concorde’s top speed.

The flight plan

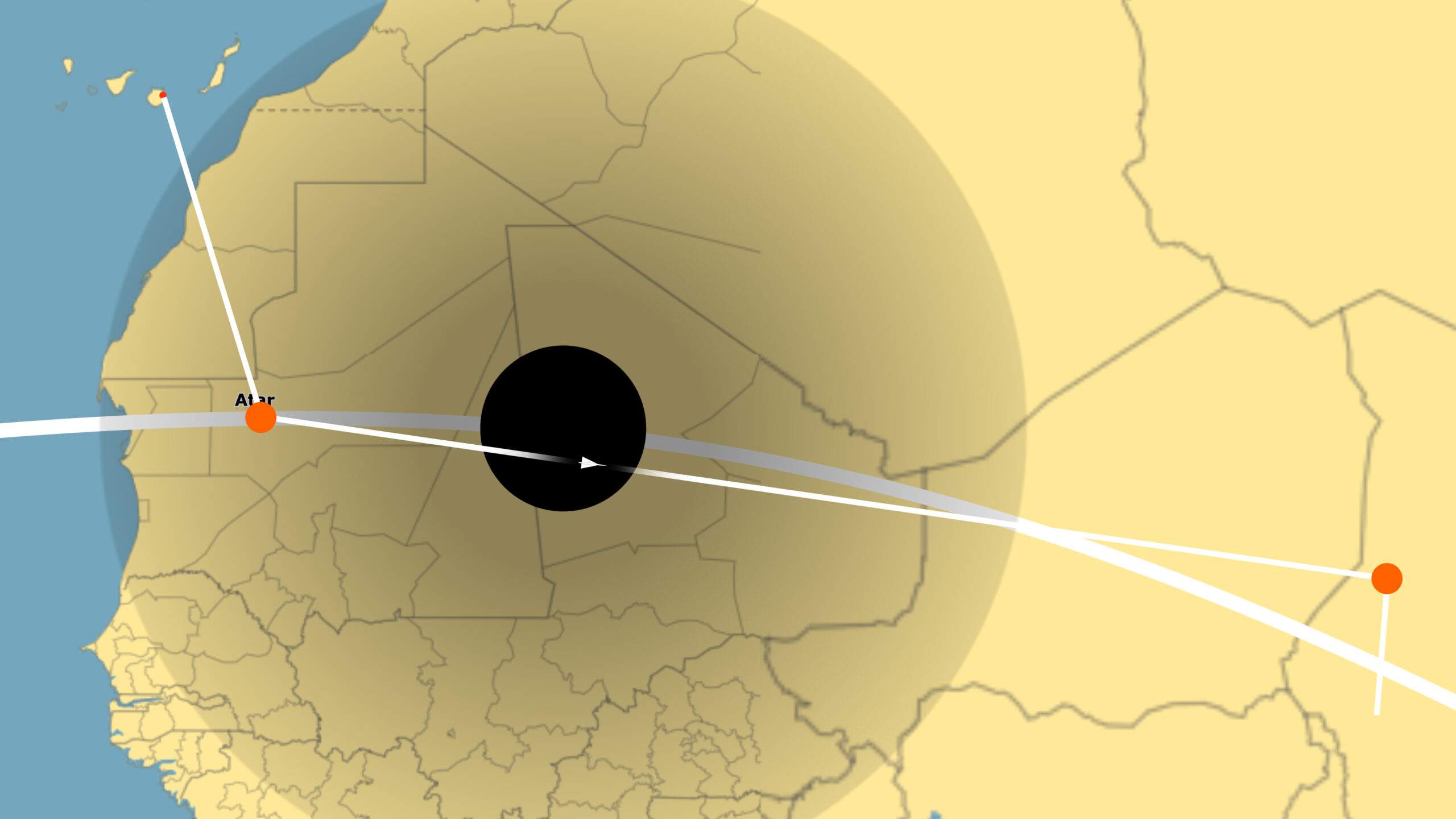

In order to stay in the Moon’s shadow for as long as possible, Concorde had to follow a very precise flight plan. The best chance for achieving this was over Africa, but this didn’t give the team a whole lot of options for airports. Most of the runways in Africa were too short for Concorde – and the hot conditions meant that Concorde would have to carry less fuel during takeoff, minimizing their time in the shadow. They eventually settled on the island of Gran Canaria, which had a cooler climate and a great runway.

The plan was to take off, fly South and intercept the Moon’s shadow at a specific point over Mauritania where it would turn and follow the shadow across the Sahara desert. But the path of the shadow wasn’t straight and instead followed a large curve. This would make science observations from inside Concorde very difficult if it had to constantly make turns. And so Pierre and his team came up with a straight line path that would touch the northern edge of the shadow, cut across to its southern edge and end at its northern edge. This would give them up to 80 minutes in the shadow without having to make a single turn.

Since the shadow would be traveling a little bit faster than Concorde, it would eventually outrun it. And so, the team had to meet the shadow at a precise point on the shadow’s leading edge. If they were to arrive more than 15 seconds late or a kilometer off, they would fall out of the shadow much sooner, and their time in totality would be drastically reduced. But arriving at the intercept point so precisely with all the variables of weather would be a huge challenge. Luckily, Andre Turcat was one of the best pilots around – and he knew Concorde better than anyone.

The team of scientists

With a solid flight plan, Pierre recruited 4 other teams of scientists that would each carry out experiments onboard Concorde. Since Concorde was going to fly over the equator, the eclipse would be directly above the aircraft. And so holes were cut into the roof of Concorde and special windows were installed to give the scientists a clear view of the eclipse. All of the seats were removed from the cabin and the electrical supply was modified to provide power to the science instruments. After weeks of modifications, the fastest science observatory in the world was ready to make history.

Takeoff

On the 30th of June, at precisely 10:08 in the morning, Concorde began rolling down Runway 21. Turcat had decided to take off 20 seconds early, giving him time to correct for any headwinds that might slow Concorde down. This turned out to be a wise choice, since the weather that morning was more turbulent and they ended up losing 8 seconds during the climb up to altitude. With 12 seconds of time still to lose before reaching the intercept point, Turcat started deploying small airbrakes to carefully bleed off some speed. This quickly brought them closer to the correct arrival.

But the winds continued to be unpredictable and Concorde slowed down too much, falling 4 seconds behind the scheduled arrival time with just a few minutes to go. In order to make up for this, Turcat briefly pushed the engines past their maximum operating speed of mach 2.2 and Concorde arrived at the intercept point just 1 second late and only a kilometer off course.

At the exact same time, the Sun fully disappeared behind the Moon and Concorde was now in complete darkness. Despite it being midday, the stars became visible and the scientists could see the Sun’s corona through their windows. Concorde was now racing against time and the Moon itself – and so the scientists got to work.

What did they discover?

Pierre and his team had developed a telescope that could measure the infrared light coming from the Sun’s corona. During the 74 minutes in the Moon’s shadow, they made measurements that furthered our understanding of the zodiac light, the layer of dust in our solar system that gets lit up by the Sun.

The team from the US discovered that the Sun’s corona has acoustic waves which cause it to pulse every 5 minutes.

Concorde flew perfectly for 74 minutes before it left the Moon’s shadow and landed in Chad. For the scientists and pilots onboard, they got to witness one of the most beautiful spectacles from the most unique vantage point. This remains the longest eclipse experienced by humans, a record that will most likely remain for centuries.