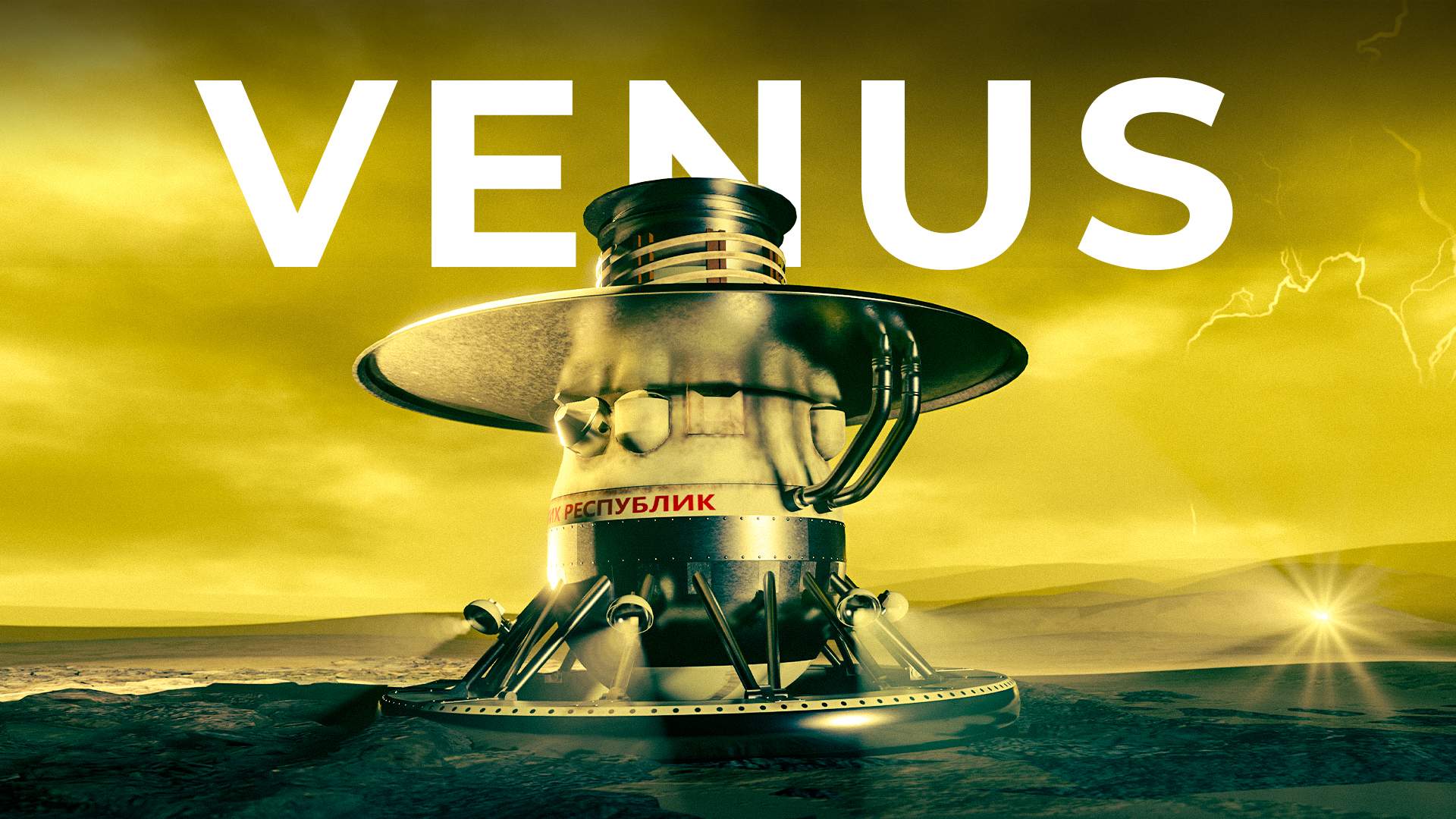

Venera 4 entered Venus’ atmosphere in October 1967. At the time, very little was known about this mysterious planet – but scientists believed that under its thick layer of cloud was a world not too different from Earth, with a similar 1 bar atmosphere and Earth-like temperatures. But little did they know what kind of world this poor little space probe was about to enter.

Venera 4

As it hit the atmosphere at 40,000km/h, its parachute deployed and the antennas started sending back data. At first, the atmospheric pressure was similar to Earth’s, and the temperature was around 30 degrees. But as it descended further into the atmosphere, the readings started to go crazy. One atmosphere quickly became 10, 10 became 20 and the temperature was well over 200 degrees when suddenly… The space probe cracked open under the intense pressure and all communication was lost.

The last bit of data it sent back revealed an atmosphere that was 22 times thicker and 250 degrees hotter than anywhere on Earth. It also showed that it was made almost entirely from carbon dioxide with toxic clouds of sulphuric acid, turning the sky yellow. The crazy thing is, the data cut out way before Venera reached the surface, so scientists had no idea how much worse it got.

At this point, no spacecraft had ever landed on another planet – and Venera 4 was just one in a series of many Soviet space probes that had failed to land on Venus. But now that the Soviets knew just how harsh Venus really was, they were even more determined to get there. But building a spacecraft that could survive this deadly environment for long enough would be a huge challenge.

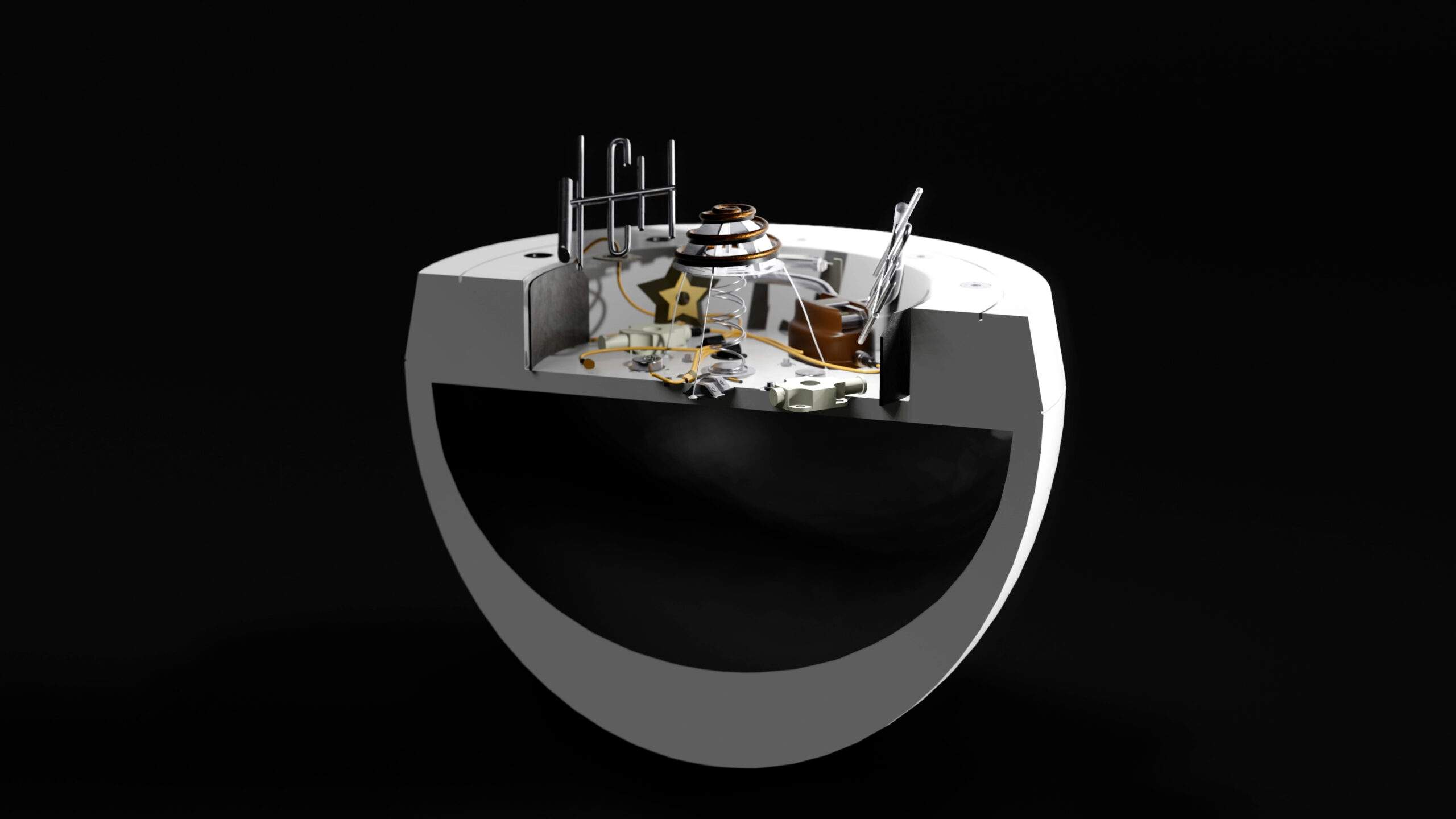

Early Venera space probe design

The early space probes had a relatively simple design. The lander was a 1 meter wide titanium sphere, pressurized inside to around 25 atmospheres. It had a handful of scientific instruments to analyze the atmosphere and a battery to power it during descent.

The lander had no thrusters – and instead used its own drag and a series of parachutes to bring it down to the ground. But with Venus’ thick atmosphere, this turned out to be a problem.

Instead of quickly falling through the atmosphere in a matter of minutes, Venera 4 hit the atmosphere like a brick wall, and quickly slowed down to just 18km/h, much slower than expected. This meant that the spacecraft had to endure 90 minutes inside Venus’ atmosphere, constantly being exposed to the ever increasing heat and pressure until it was crushed.

The Soviets realized that once they entered Venus’ atmosphere, time was limited. And if they wanted to get to the surface, they would have to pass through the atmosphere quickly, before it had time to crush or melt the lander. And so the Soviet engineers completely rethought their approach to Venus.

Redesigning the Venera space probes

In order to reach the surface of Venus before being destroyed, the Soviets redesigned the space probe to make it fall through the atmosphere more quickly. They added a cord to the parachute that would stop it from opening, allowing Venera to fall much faster. It was made of a material that would melt at 200 degrees, and so the parachute wouldn’t open until the probe was much closer to the surface.

Since the pressure on the surface was still unknown, the engineers went overkill with Venera’s protection. The walls were two times thicker and the space probe could now withstand a pressure of 180 atmospheres.

After 3 years of rethinking their approach to Venus, the Soviets were ready to put Venera 7 through hell. As it hit the atmosphere, the lander slowed all the way down and deployed its parachute. The cord did its thing and allowed the space probe to quickly fall through Venus’ thick atmosphere. The probe was now much closer to the surface than any of the previous missions, until… With just 3 kilometers to go, the parachute tore itself apart, and the probe started plummeting to the ground, slamming into the surface at 60km/h.

Venus’ hellish atmosphere

The Soviets had another failure on their hands… or so they thought. A few weeks later when reviewing the data, they noticed that a very weak signal had actually been transmitting for 23 minutes after the lander hit the surface. As it turned out, the lander actually survived, but it had been knocked onto its side, making the antenna’s signal to Earth extremely weak. Incredibly, the last bit of data it sent out showed that the temperature at the surface was a mind boggling 500 degrees.

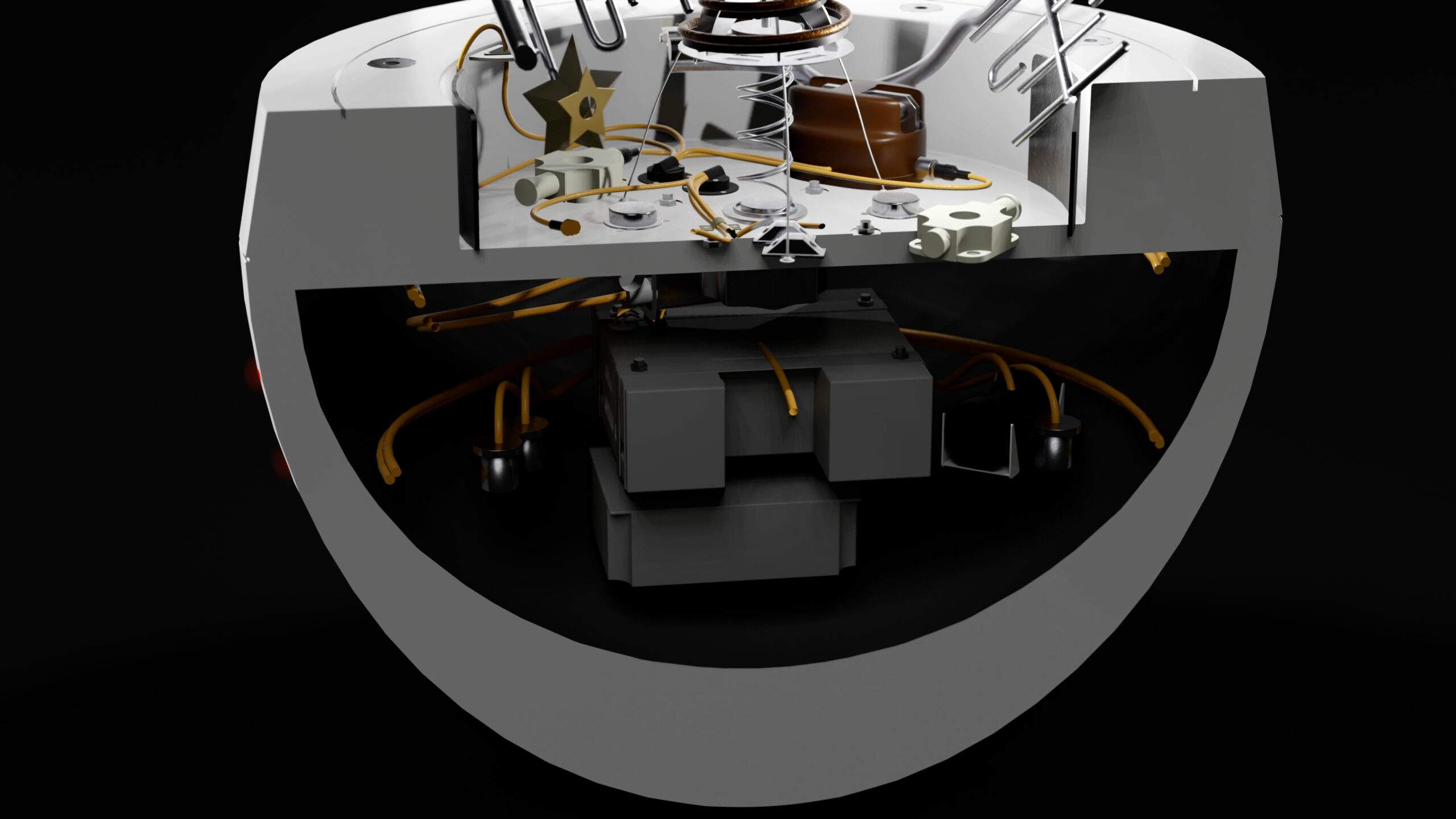

Venera 8 cooling system

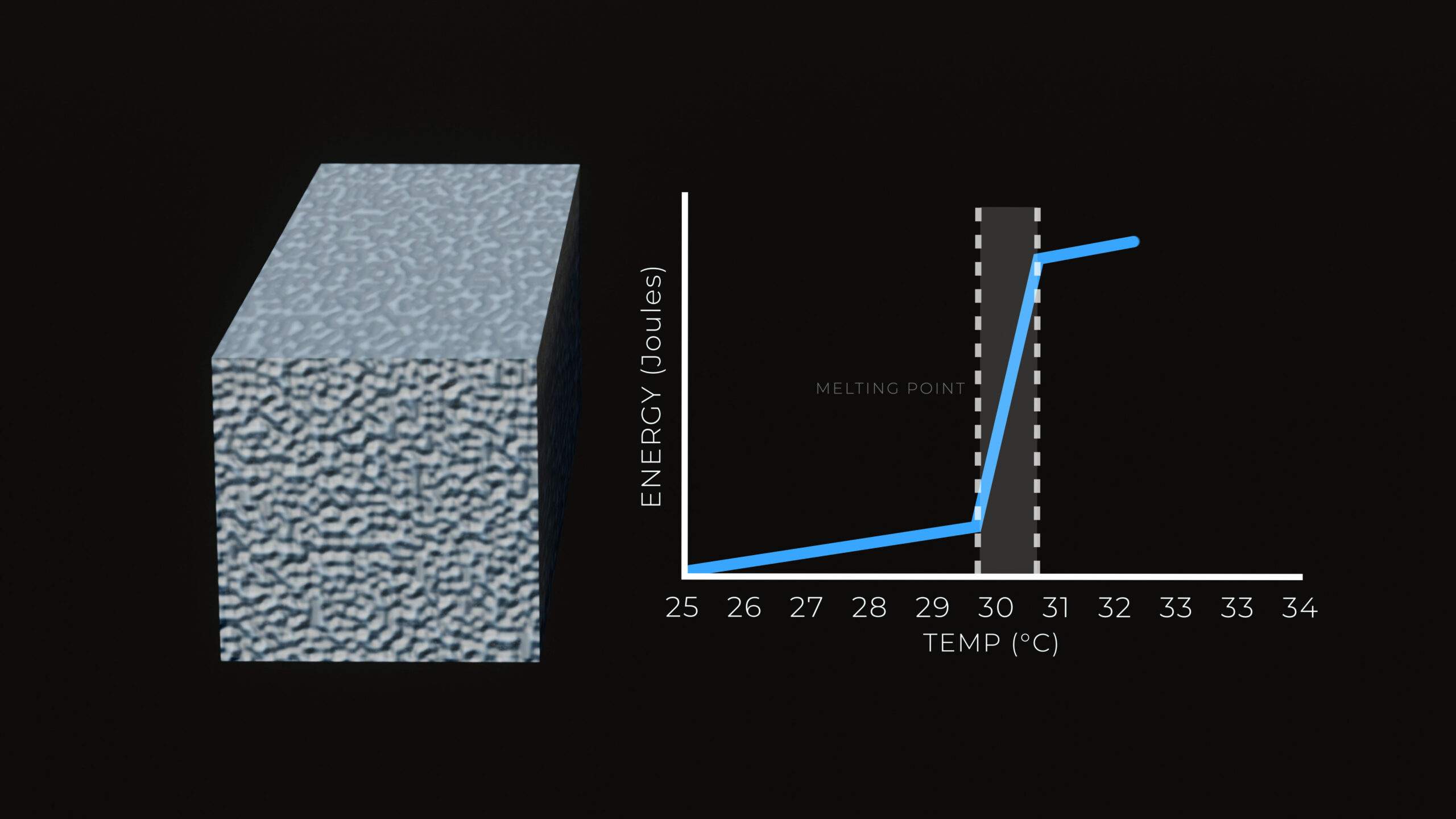

Since temperature was now the main problem limiting their time on the surface, the engineers came up with a genius but simple cooling solution for Venera 8. Inside the space probe were blocks of lithium nitrate, a salt-like substance which has a very high heat of fusion. This is the amount of energy required to turn it from a solid into a liquid.

In order to heat this material up by one degree takes just under 2 joules of energy per gram. But when it reaches its melting point, crossing that boundary from a solid into a liquid takes almost 300 joules of energy. And so this change from a solid to a liquid absorbs a large amount of heat energy, which is effectively stored in the material until the liquid is turned back into a solid. And so blocks of lithium nitrate were placed inside the lander to absorb heat and take it away from the electrical components.

Since the Venera probes were going to die anyway, actually getting rid of that heat wasn’t important – the lithium just needed to absorb the heat for as long as possible.

This system worked extremely well and Venera 8 successfully touched down and survived an entire hour on the surface. The Soviets had now mastered the art of getting to Venus. But the world still had no idea what this crazy world actually looked like.

Taking first pictures of Venus’ surface

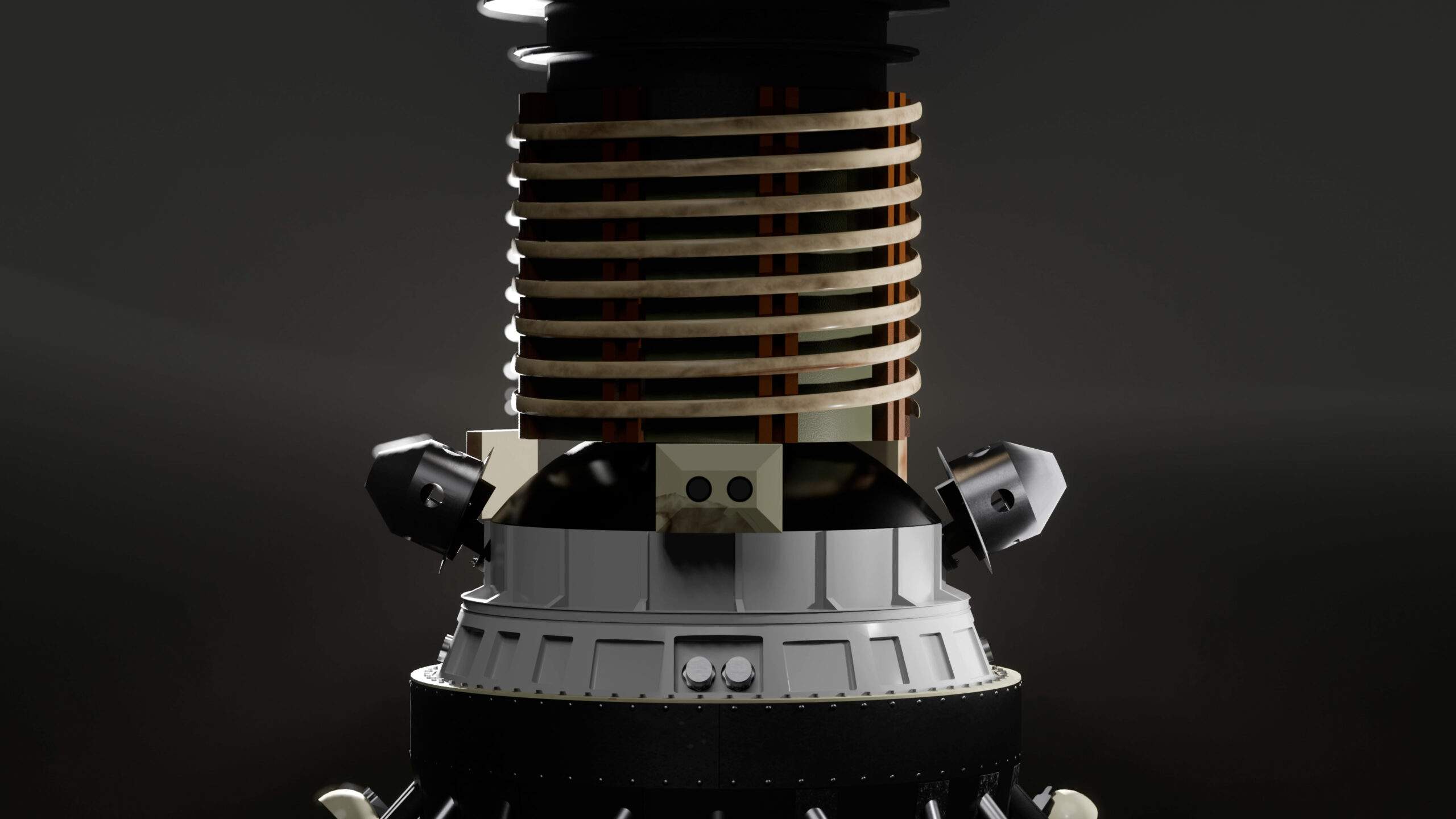

And so it was up to Venera 9 to take the first pictures on Venus. For this mission, the lander was completely redesigned once more. Instead of using parachutes for the final descent, Venera 9 had a large air brake to slow it down and a set of landing legs to absorb the impact. But the most important feature on Venera 9 was the camera system.

It had two moveable cameras on either side of the lander that could take a 360 degree panorama of the surrounding landscape. But designing a camera that could survive the intense pressure and temperature of Venus was yet another challenge.

Venera 9’s camera system

The cameras were placed inside the lander’s pressure vessel and two periscopes stuck out into a super thick quartz pressure window. At the end of the periscope was a small lens that could rotate and scan the 180 degree view of the surface. The light would travel down the periscope and through a lens that would correct the effect of the thick pressure window. Each of the two cameras had large lens caps that were designed to pop off once the probe had landed. On Venera 9, only one of these worked. This was the very first picture taken on Venus.

On future missions, the cameras were improved, eventually taking higher definition color images. On Venera 14, a microphone was placed onboard. The following is real audio of the probe landing on the surface and an instrument drilling into the surface.

All-in-all, the Soviets landed on Venus 8 times, with each mission sending back incredible images and scientific data about this mysterious planet. An achievement we’ve yet to repeat some 50 years later.

please

well i guess im the second. but from that it is intresting the soviets took 8 times to land on venus but i wonder what rockets they were launched from and if humans will ever set a foot on venus probablly not and im 9 btw