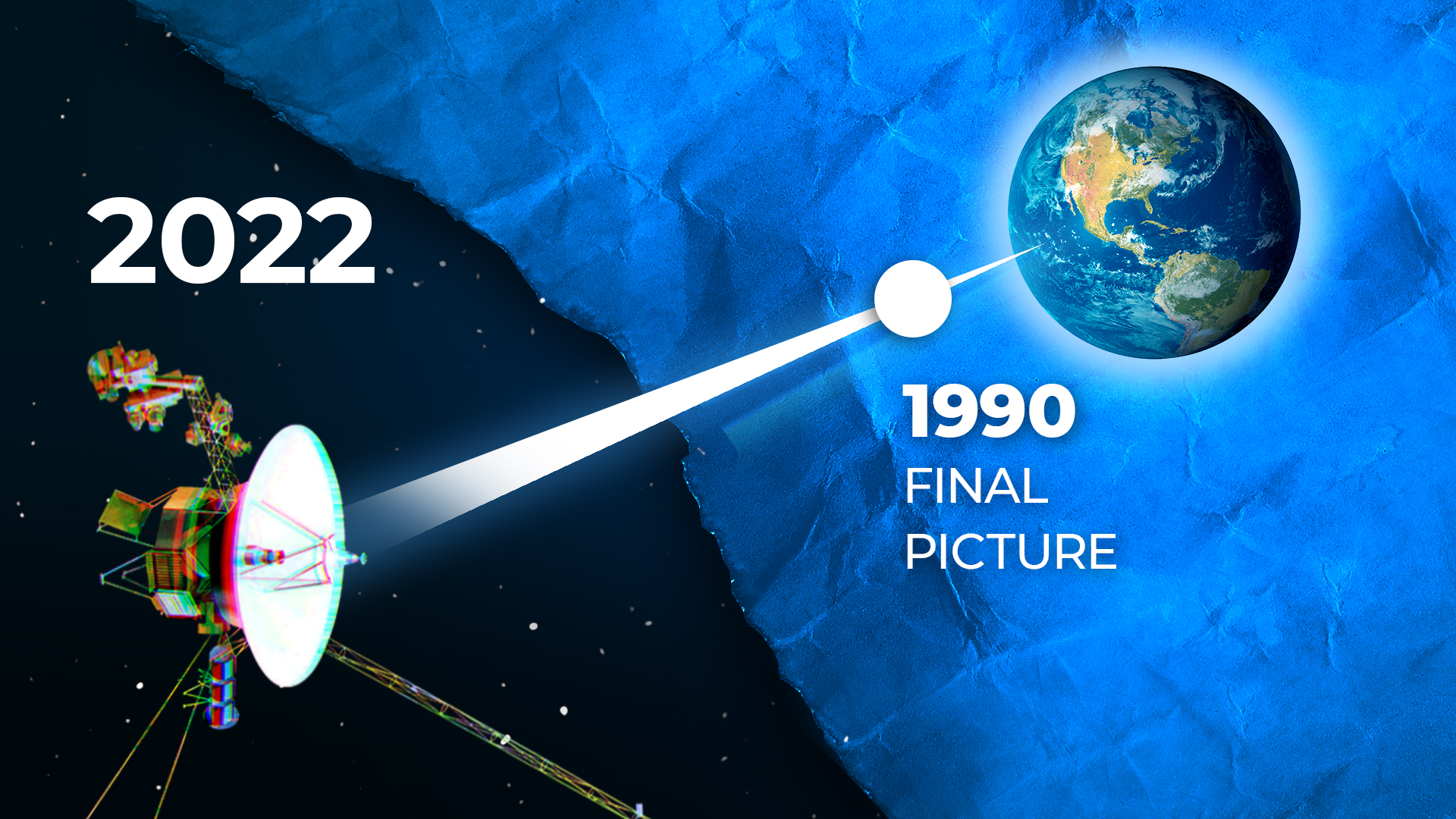

This is the famous pale blue dot image taken by Voyager 1, showing our Earth as a tiny pixel, 6 billion kilometers away. This picture was taken before many of you were even born, but the elements and materials that made us are all contained in that tiny blue dot we call home. But this date is significant.

Just 34 minutes after this picture was taken, the cameras were switched off forever, leaving Voyager 1 completely blind. Since then, the spacecraft has become the furthest man-made object in space, now at a point 24 billion kilometers from Earth.

But why were the cameras turned off? And what would it take to turn them back on?

The Voyager space probes have broken so many records during their time in space. Not only are they the furthest objects in space, but they’ve also been operating for the longest amount of time, over 45 years.

It’s incredible to think that after all that time spent in the harsh environment of space, the computers and systems that were designed here on Earth in the 70’s are still functioning. Voyager is powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG). This is basically a nuclear battery that can last for a very long time. These are very common on spacecraft and it’s why Voyager has been able to run continuously for over 45 years.

Voyager 1 was filled with technology that was way ahead of its time, and a perfect example of that is the camera system.

Voyager 1 camera technology

Voyager 1 has two vidicon cameras onboard which are essentially very early television cameras using analog to digital technology. They had an effective resolution of 800 by 800 pixels and captured 8 bit images in grayscale.

One had a wide angle lens for capturing the planets in full detail as the probe passed close by. The other had a narrow angle lens which was zoomed in and could capture the smaller details of each planet it observed and of course, look back at our solar system as it grew smaller and smaller on the horizon. As always, fitting stuff onto a spacecraft is a complex process, as everything has to be made as small and as light as possible. These cameras didn´t produce the sharpest images and they were only black and white.

However, before the light reached these cameras, it went through an optics system that allowed it to form colored images.

This was a filter wheel that contained violet, blue, green and orange filters. Voyager would take multiple images of its subject using each of its filters. As light passed through the filter, it would only allow light from that color to pass through, the other colors would be absorbed.

The images were still taken in grayscale, but each image would have areas with different amounts of brightness, where the light was more sensitive to a certain color. Once these images were sent to Earth, they were saturated with their respective filter color and combined to form a full color image.

This is essentially how the human eye works, since our eyes have three color sensing cones: red, green and blue, which are combined to give us vision with a range of colors. But with Voyager, the real magic happens inside the vidicon tube.

Voyager´s Vidcon Tube

After the light passes through the lens and filter wheel, it enters into the vidicon tube. The first thing the photons hit is a see-through faceplate, made from a layer of tin-oxide, which has a photoconductive target plate just behind it. When the photons hit the target plate, free electrons are created.

The higher the intensity of light on a given point, the more free electrons are created. These free electrons are then attracted to the faceplate, leaving behind gaps on the target plate. After this, a cathode at the back of the tube fires electrons towards the target plate to scan the image.

These electrons reach the target plate and fill in the gaps, creating an electric current. This signal contains the image data and can now be transmitted back to Earth.

Sending pictures back to Earth

We’ve seen how Voyager’s cameras convert the light into a signal, but what happens after that? This wasn´t an ordinary film camera where each picture could be processed here on Earth. Each image that Voyager captured would take up around 5 million bits of information – or just over half a megabyte.

This doesn’t sound like a lot by today’s standards, but when your spacecraft is billions of kilometers away, sending that data back is extremely difficult. Back in the day when Voyager 1 was much closer, it had a maximum data rate of around 115,000 bits per second. At this rate, it would take about 43 seconds to send an entire image back to Earth.

Now, the data rate is only around 160 bits per second, meaning it would take over 8 hours just to transmit one image. On top of that, Voyager 1 is now 23 billion kilometers away, so that signal would actually take 21 hours to reach us.

Since the camera can produce an image much faster than it can transmit the data, the signal from the vidicon camera is stored onto magnetic tape. This is basically an early analog harddrive. This data builds up over time and can be transmitted whenever Voyager 1 has a good line of communication with Earth. But why hasn’t Voyager’s camera been turned on in over 30 years?

Turning on the camera

To answer this, we need to look at where Voyager 1 was when it took its last picture. The famous pale blue dot image was taken from a point in space 6 billion kilometers from Earth. At this point, the spacecraft was so far away, that everything appeared as a tiny dot.

The spacecraft was also heading on a path that would eventually make it the first spacecraft to leave the solar system and reach interstellar space. So in order to know when this happened, the team wanted to prioritize the instruments that would detect interstellar plasma, a sign that Voyager 1 had left our solar system.

But Voyager 1 was already 13 years old at this point and it still had decades to go before reaching interstellar space. So, in order to still be talking with the spacecraft at that point, the engineers needed to extend its lifetime drastically.

Voyager´s power source

Like many spacecraft, Voyager 1 is powered by an RTG, which takes the heat from a radioactive material and turns it into electricity. Every year, the power output decays by about 4 Watts – and now, Voyager 1 is only producing 57% of its initial power output.

The camera system alone uses just over 40 watts of power. And so to buy the spacecraft more time, the team began shutting down various instruments onboard Voyager to reduce its power consumption.

To save memory, the team also removed the software onboard Voyager, which was responsible for operating the camera. The computers and software here on Earth that were used to analyze the images don’t even exist anymore.

And due to the cameras and their heaters being exposed to the harsh conditions of outer space for several decades, it’s likely that they wouldn’t be able to function any more. But assuming the cameras were still in good condition, what would they see if they were turned back on?

Many think that Voyager 1 is so far from the sun that it will be in complete darkness, but this is not true. Despite now being 23 billion kilometers away, the light from the sun is still 16 times brighter than the Moonlight here on Earth, so it’s definitely enough to read a book.

However, there just isn’t anything interesting or big enough around Voyager to capture on camera. If Voyager took an image today, it would be dark – but you’d still see the sun and some planets as tiny faint pixels. Perhaps the most incredible thing is that despite traveling 23 billion kilometers, the star constellations in our sky would look exactly the same.

If Voyager wanted a different perspective of our galaxy, it would need to travel thousands of light years just to see a slight shift in the stars. Voyager 1 will eventually achieve this, millions of years after we are gone and long after we have lost contact with the space probe.

Best space moment of all times: man on the moon

Why would the data transmission rate drop to 160 bits per second compared to 115,000 bits earlier in the mission? Great article, by the way.

The drop in data transmission rate from around 115,000 bits per second early in the mission to just 160 bits per second now is mainly due to the increasing distance between Earth and the Voyager spacecraft. As Voyager moves farther away, its radio signals become weaker and harder to distinguish from background noise, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR).

This is where the Shannon-Hartley theorem comes in. It describes the maximum data rate that can be achieved over a communication channel given its bandwidth and SNR. As SNR drops with distance, so does the maximum reliable data rate. To maintain communication, NASA uses slower, more robust encoding schemes that are easier to detect amid noise, even though they transmit less information per second.

So, the lower bitrate is essentially a trade-off to ensure data integrity—it’s the only way to still get usable science data from a spacecraft more than 20 billion kilometres away!