This is a scene from Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, released in 1968. This was before computers and digital effects, so how do you think he made this pen float in space?

The obvious answer is string, but this would get tangled up every time the pen rotated, and would ultimately be impossible to hide. The real trick behind this shot was simple but extremely effective.

2001 A Space Odyssey floating pen

The pen was attached to a large piece of glass with double-sided tape and placed in front of the camera. The glass was attached to bearings that allowed an operator to slowly move and rotate the glass to mimic the floating movement.

It was incredibly simple, but the end result was perfect.

This is just one of many creative tricks that allowed filmmakers to pull off crazy visual effects, all before computers and CGI. They managed to duplicate heads, make characters invisible, turn miniatures into enormous movie sets, and even invent a green-screen alternative that worked better than today’s digital methods.

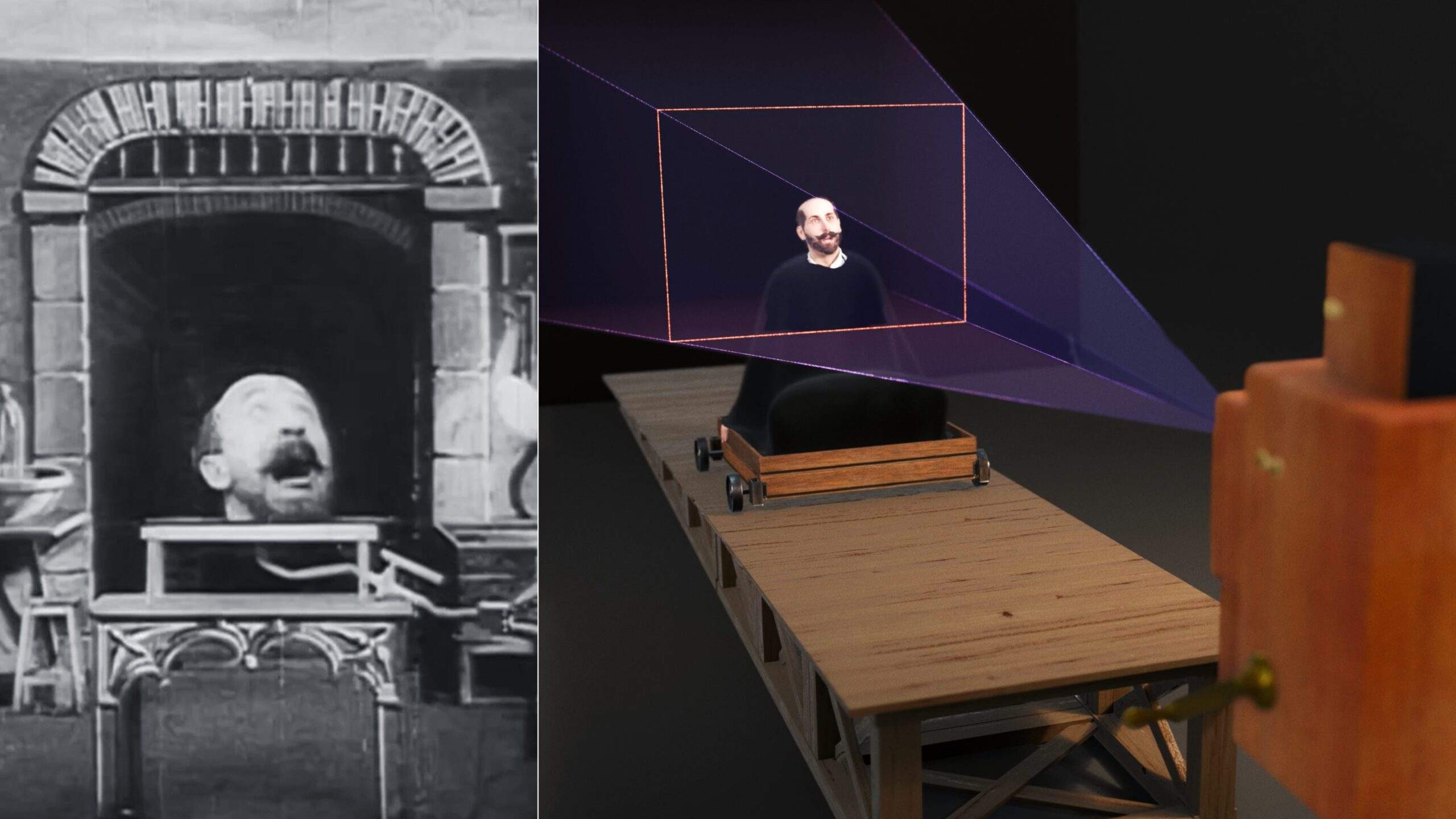

Man with the Rubber Head

This scene from “The Man with the Rubber Head” is over 120 years old, and it shows filmmaker Georges Méliès inflating a copy of his own head. But how did he pull this off in 1901?

You might think that these are two separate films layered on top of each other, but that’s not the case. In fact, everything was captured in-camera, and so what came out was the finished film, and it didn’t require extra editing.

To pull this off, he’d record the first scene with a black sheet placed in the area where the head was going to appear. Then he’d rewind the film back to the start and set up the second scene, with only his head visible against a black background. This time, he’d record directly over the same strip of film used to record the first scene.

Because this was being recorded onto a transparent film negative, the dark areas around his head essentially remained transparent, since almost no light was hitting the film. This meant that as he recorded over the original scene, only his head was exposed onto the film strip, combining the two shots perfectly.

But the real trick was how he managed to make his head grow and shrink.

The obvious idea would be to use a zoom lens to slowly make his head fill the frame. But zoom lenses didn’t exist yet.

Instead, Méliès set up a ramp where he could sit in a cart and be slowly pulled towards the camera. As he got closer, his head would grow from the neck, until it eventually filled the entire frame.

The result was incredible by 1901 standards, and this multiple exposure technique went on to be mastered in Kubrick’s 2001.

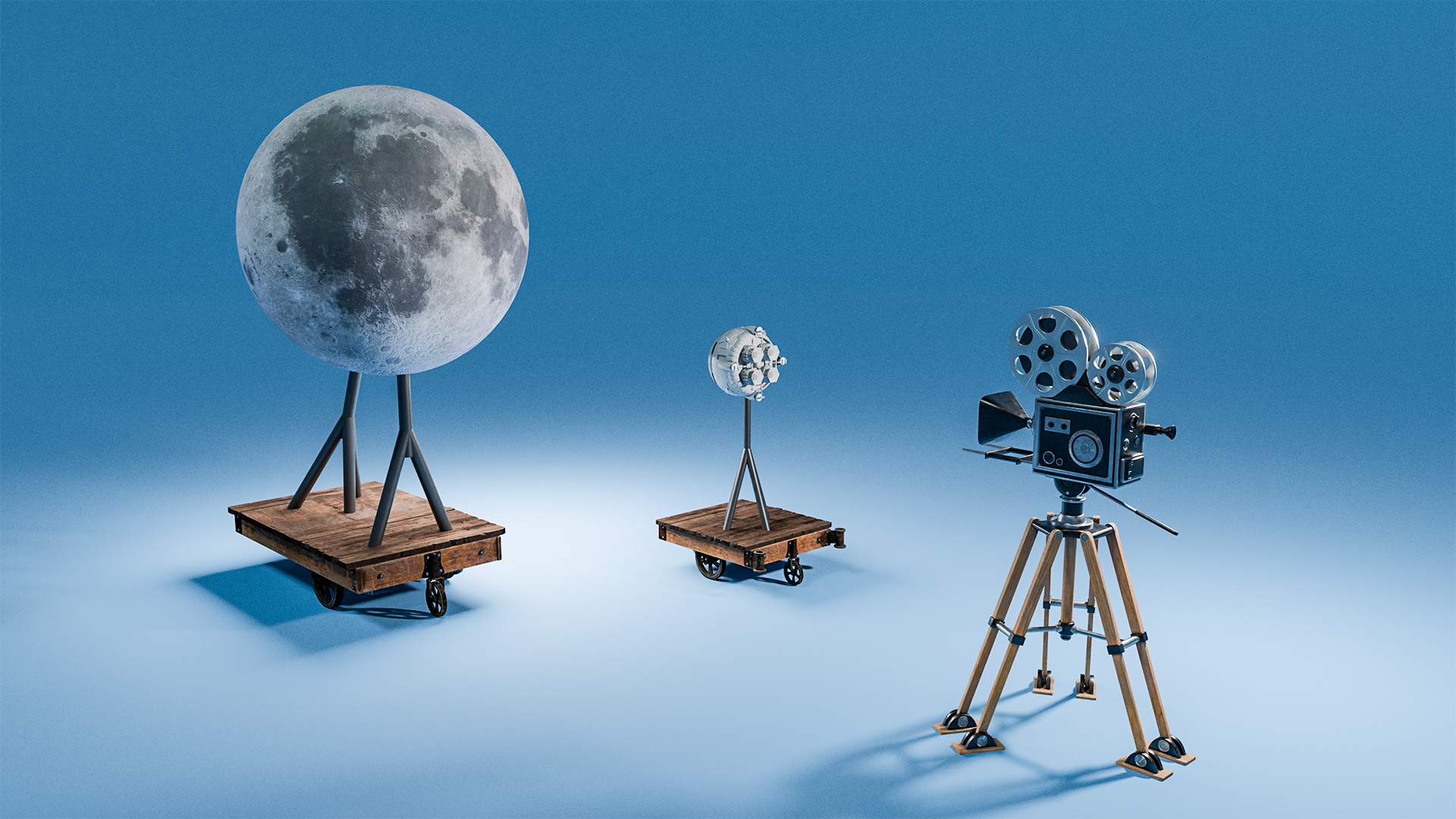

2001 A Space Odyssey space shots

For these space shots, he’d first shoot the Moon on its own, with one half of the frame being completely dark. Then, sometimes months later, he’d rewind the film and record the spacecraft shots directly over the same strip of film.

By doing it this way instead of combining separate films into one, there was no quality loss, and the film that came out of the camera was essentially the finished shot, as if the Moon and the spaceship had been filmed together.

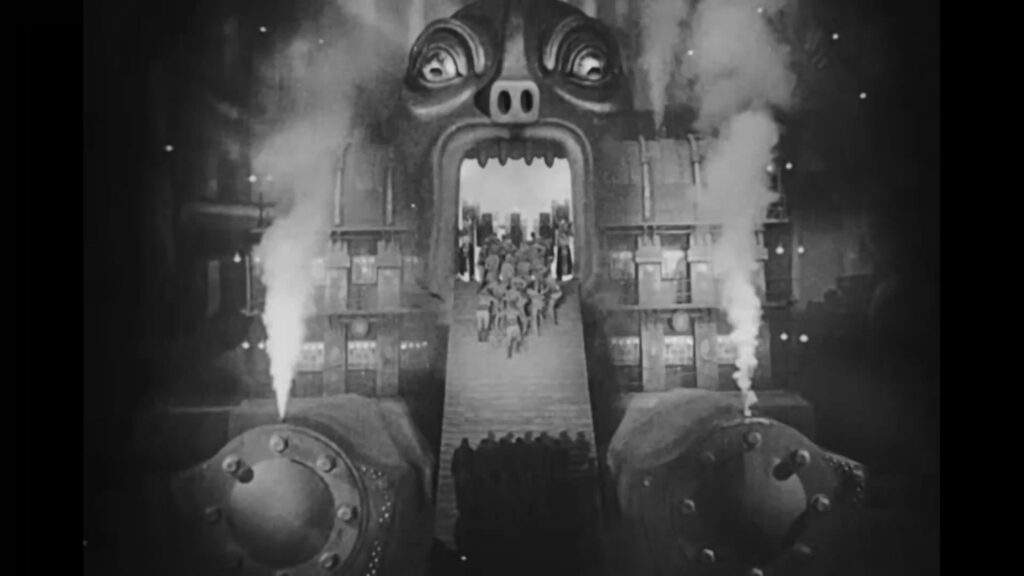

Metropolis

Filming everything in-camera was another key feature of this next trick from the 1927 classic Metropolis. These scenes placed real actors into enormous futuristic-looking sets. But not only was this all done in-camera, it was all done in one take, without the need to record over the film strip.

For this shot, the actors were walking down a platform far away from the camera, in order to appear much smaller.

Then directly in front of the camera, they placed a mirror at 45 degrees, which reflected a detailed miniature model of the futuristic city into the camera. By cutting out a very precise portion of the mirror, it allowed the camera to see through the mirror to the actors in the distance.

The same trick was used for this scene.

The massive demon mouth wasn’t massive at all; it was actually a much smaller miniature just off to the side of the camera. But when everything lined up perfectly, it looked like the actors were walking straight into its mouth.

Ben-Hur

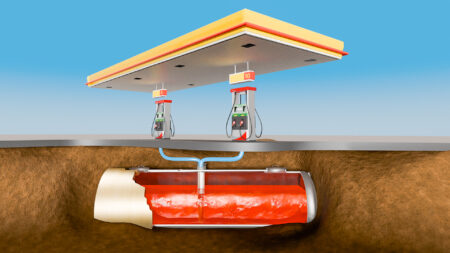

Just two years before this, the movie Ben-Hur pulled off a similar trick of turning miniatures into massive sets, but without the use of mirrors.

These epic chariot racing scenes required an enormous colosseum, filled with crowds. But the studio didn’t have the budget or time to build a full-scale set. Instead, they built the bottom half of the set for real and faked the rest with miniature sets hanging in front of the camera.

By placing them close to the camera, these miniatures became enormous movie sets, matching the scale of the real set perfectly. The miniatures even had fake audience members that could be mechanically moved up and down to simulate a cheering crowd.

The Invisible Man

These tricks were all about adding more things into the scene. But what if you wanted to make something disappear? That’s exactly the kind of trick that was mastered in the 1933 movie “The Invisible Man”. The main character drinks a potion that makes him invisible, and he ends up going on a rampage while the police try to track him down.

Throughout the movie, multiple exposures were used to make the man invisible, but it’s this shot of the man running through snow that we’re going to look at.

In order to pull this off, a fake wooden floor was created and footprint-shaped holes were cut into the wood. The floor was covered in powdered snow, and one by one, the wooden cutouts were released, causing the snow to fall and make footprints in the ground.

This blew people away in 1933, and the invisibility effect looked incredibly realistic.

But what about scenes that aren’t meant to look realistic at all? – like these scenes from Kubrick’s 2001.

2001 A Space Odyssey Stargate shots

These shots were so abstract that they couldn’t be achieved by simply pointing the camera at something. In order to pull it off, the visual effects supervisor had to get inventive.

He placed the camera on rails and pointed it towards a black screen with a thin slit in the middle. Behind the screen was a super long piece of artwork that was backlit by bright lights. The camera was tilted slightly off-center, so that when it moved forward, the slit would travel from the middle of the frame to the edge of the frame.

By keeping the shutter open for the whole duration of the move, it created a streak of light across the frame, just like when you take a long-exposure image of a car at night.

As the camera moved forward, the colorful background would move a few inches to the right, revealing different parts of the artwork throughout the streak. This single movement only created one frame, and so the process had to be repeated hundreds of times to get the full sequence.

To record the other half of the frame, the camera was tilted in the opposite direction and the entire process was repeated, using the multiple exposure trick to record directly onto the original film. The amazing thing is, this machine was completely automated, and it ran constantly for several hours at a time to create these shots.

But perhaps the most impressive of all of these techniques is one that no longer exists, but was so perfect that even digital techniques today struggle to match it.

Sodium Vapor technique

You’re probably familiar with green screens – put anything in front of one, key out the background and replace it with anything you can imagine. This trick has been around since the 1940s, when it was more common to use a blue screen.

But this whole technique had major drawbacks that still exist today: actors were constantly surrounded by this horrible blue glow, any kind of motion blur would reveal the blue background, detailed parts like hair would lose their sharpness and transparent objects simply became invisible.

The problem is, that even if the background is perfectly blue, the camera doesn’t see it that way. Areas close to the actor blend together and become vastly different shades of blue. Even with modern digital techniques, it’s almost impossible to avoid these problems when keying out backgrounds.

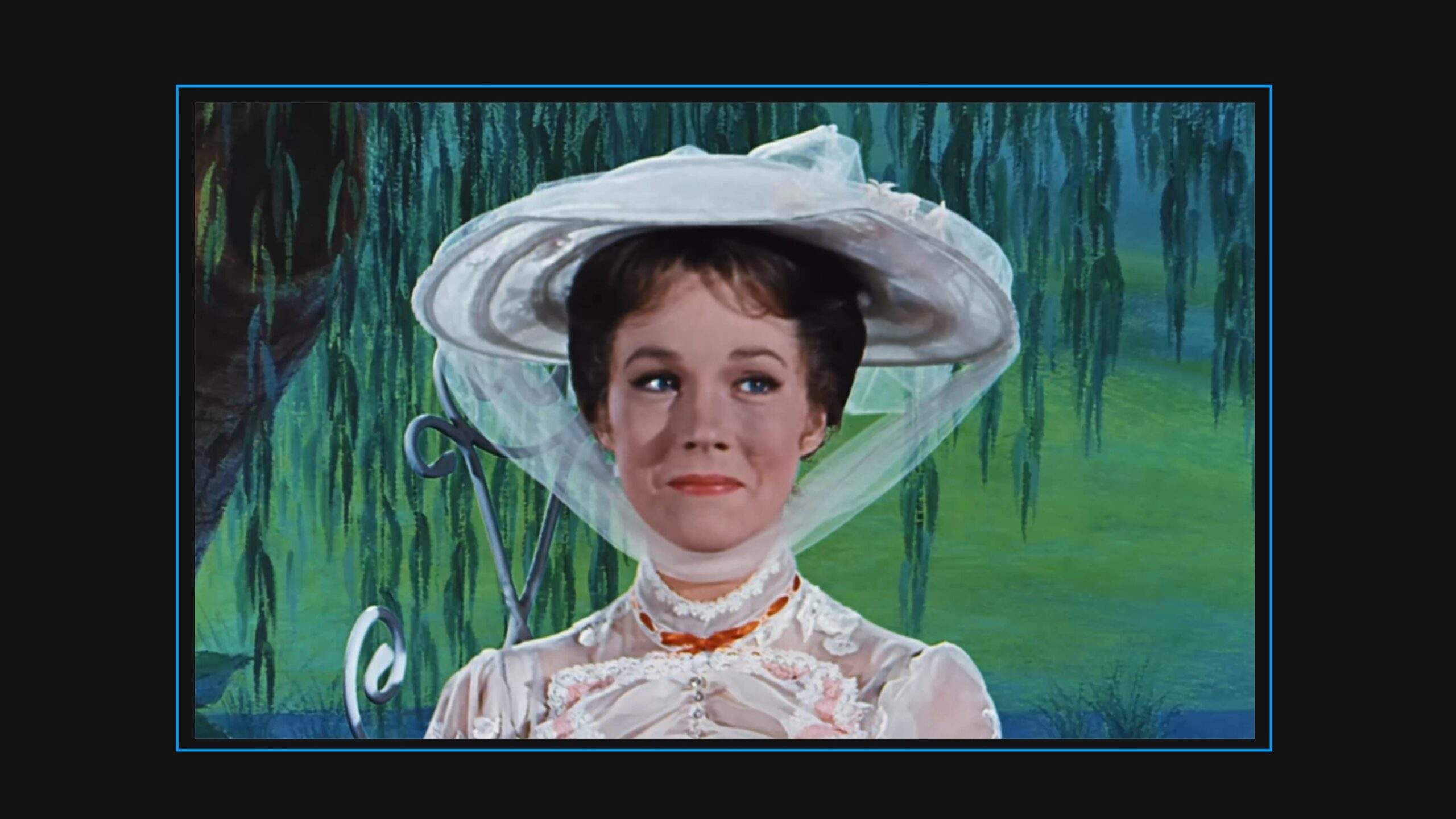

But in the 1964 movie Mary Poppins, Disney somehow nailed this effect. The semi-transparent veil blends in perfectly, the salt leaves no trace, and the actors are even wearing blue and green clothes throughout the movie. The edges are so perfect, better than almost anything that’s possible today, so how did they do it?

Instead of a blue or green screen, the actors were standing in front of a white screen, which was lit by powerful sodium vapor lights.

These lights emitted a very specific wavelength of light at 589 nanometers, and so it was very easy to separate only this wavelength, without affecting any other colors.

Inside the camera was a special prism with a coating that was extremely sensitive to this exact wavelength. As the light entered the camera, the regular color light passed through onto a strip of film, but the sodium light was separated and directed onto a different strip of black-and-white film. The result was a black-and-white silhouette that perfectly masked the shape of the actors.

This silhouette could be used as a transparency mask – essentially, everything that was white became transparent and everything that was black remained in the shot. But it wasn’t just black or white. For blurry or semi-transparent areas, the silhouette matte would be a shade of gray, and essentially allow some of the original image through.

If the original footage had been filmed on a bright blue background, this would simply allow part of that blue to leak through.

The reason this worked so well is because on the color film there was essentially no background at all. It didn’t detect the sodium light, and so almost no light from the background would end up on the film strip. When it came to those semi-transparent areas, there was no light beneath the matte to shine through, creating perfect transparency.

By the 80s, this technique was largely forgotten about, since it was almost impossible to replicate the prism. Nowadays, digital effects have taken over the film industry, but it shows just how much creativity went into the magic of these old movies.