November 18th, 1987. Like every night on the London Underground, it’s packed. A train on the Piccadilly line has just pulled into King’s Cross, one of Britain’s busiest stations. The hoard of passengers get off, but as they squeeze their way up the old wooden escalators, one passenger notices a strange glow coming from within the escalator. It’s on fire.

10 minutes later, the London Fire Brigade arrive on the scene, to what is now a small escalator fire, nothing they haven’t dealt with before. But in a matter of seconds, the entire escalator suddenly ignites, sending a jet of fire upwards and into the ticket hall, killing 31 people inside.

Figuring out what exactly happened here was mind-boggling, and it led investigators down a 7 month rabbit hole until they discovered an unexpected physical phenomena, completely unknown until this point, that allowed the fire to behave in mysterious ways.

Investigating a fire

Even in a large fire, buildings usually don’t burn all the way to the ground. Firefighters normally arrive in time to control the fire, leaving behind a scene full of clues and evidence that can lead investigators to the source.

They start outside the building and rule out the areas where the fire couldn’t have started. If the back of the house is completely charred but the garage is perfectly fine, it’s safe to say that the fire probably didn’t start in the garage.

By systematically narrowing down the search to the rooms with the most damage, they can start looking at the details.

Fire burn patterns

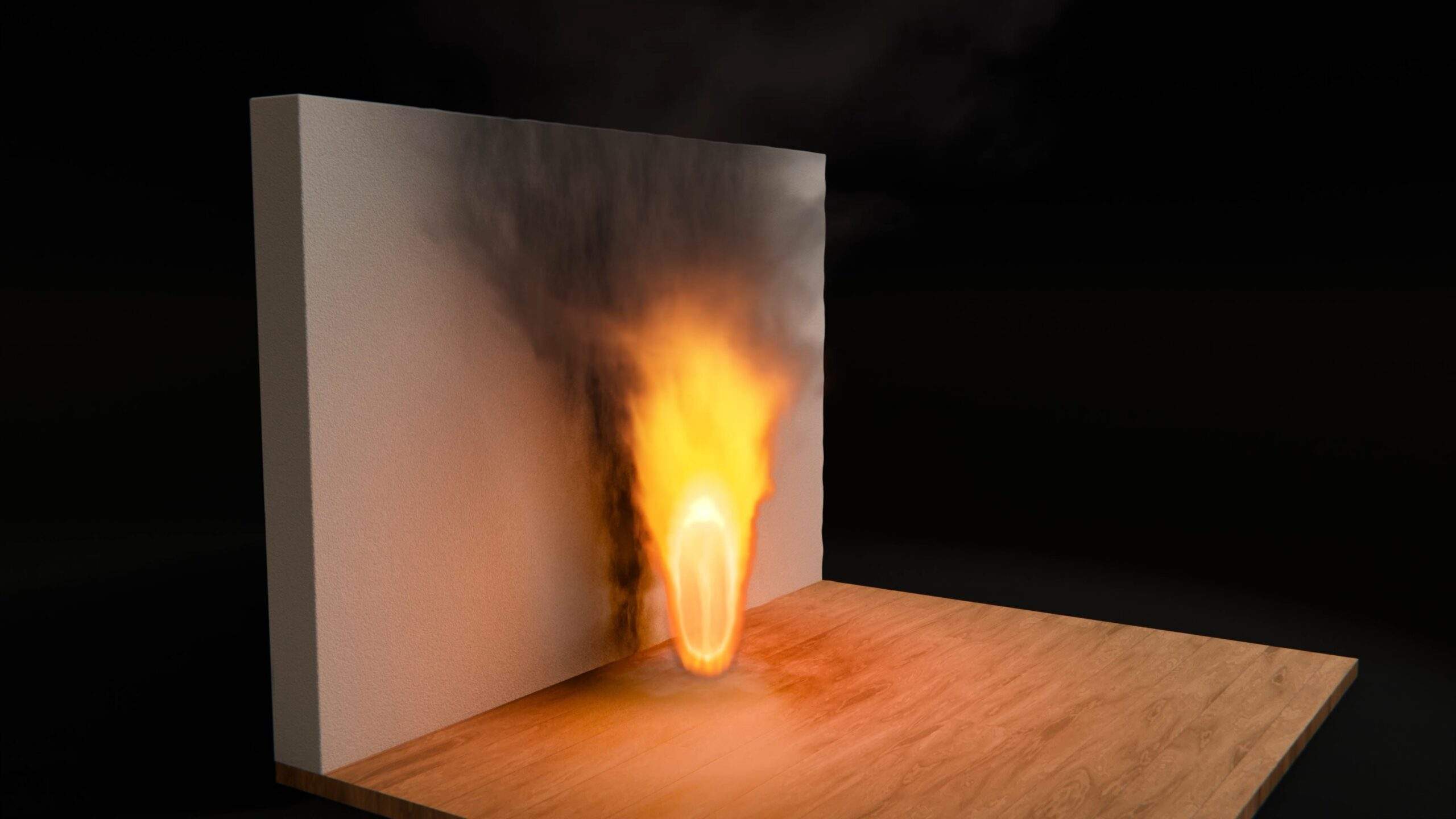

Fire burns upwards and outwards, and so when an object burns next to a wall, it creates a distinct V shape that widens out closer to the ceiling. If the object is slightly further from the wall, it creates more of a U-shaped burn mark, since the tip of the fire doesn’t touch the wall.

In a small simple fire that gets put out early, these burn patterns usually point directly towards an obvious source of the fire. But things aren’t always so simple.

In reality, once a fire spreads to multiple objects, these burn patterns start blending together.

On top of that, fire can get pulled towards openings like doors and windows, where the abundance of oxygen helps the fire grow. This can leave some areas of the room looking more damaged than the actual source.

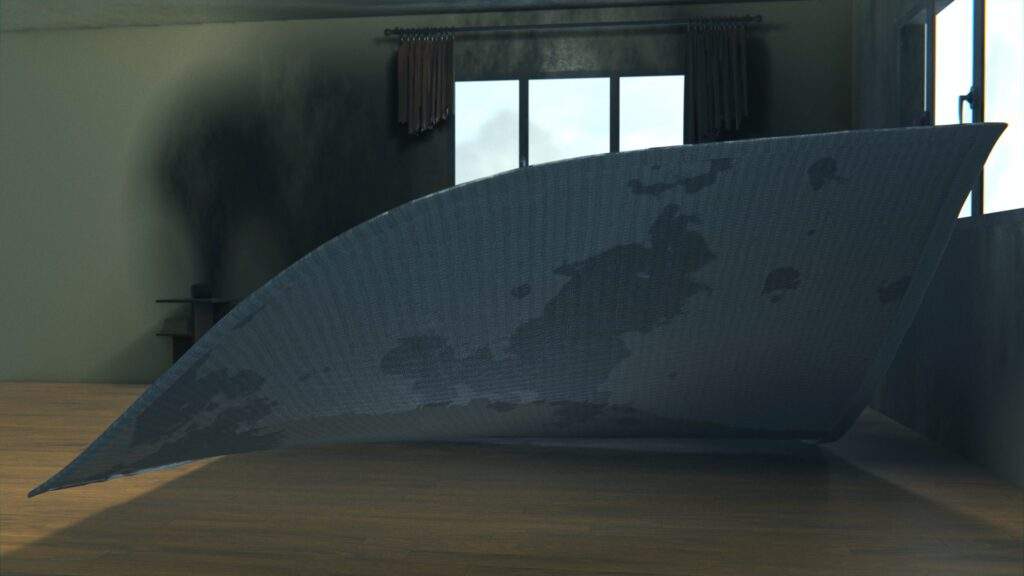

Take a look at this room for example, is it obvious where the fire started? We can see multiple V patterns on the left, but the area on the right looks more burnt. It’s possible that the fire started on the left, but worked its way up the curtain, dropping burning debris onto the sofa. Then eventually, the window smashed with the heat, and allowed fresh oxygen to flow in, drawing the fire towards that side of the room.

But wait, if you lift up the carpet, you’ll see what looks like liquid stains. This can be a sign that something like gasoline was used to quickly and deliberately start the fire. If an investigator suspects arson, they can send in a sniffer dog, specifically trained to sniff out these kinds of flammable substances.

If none of this leads towards an obvious source and there’s no obvious sign that the fire was deliberate, the investigators will look towards the objects themselves.

Although many things get completely destroyed in a fire, a surprising amount of stuff survives – and exactly how it survives can give the biggest clues.

Charring

When materials reach a certain temperature, the water molecules and other organic compounds inside turn into gas, leaving behind a layer of carbon. This is known as char.

As the material keeps burning, it works its way inwards towards the fresh unburnt material, leaving behind a thicker and thicker layer of char over time.

And so, by measuring the char depth of similar materials at various points in the room, investigators can build up an image of which areas started burning first. This doesn’t give a definitive result, but it can help rule out certain areas and lead them closer to a possible source.

But what happens when a fire defies all of these rules?

What caused the King’s Cross fire?

In the London Underground fire, eye witnesses reported the fire behaving in strange ways. It wasn’t burning upwards, but at an angle, perfectly horizontal to the escalator. This baffled the investigators for months.

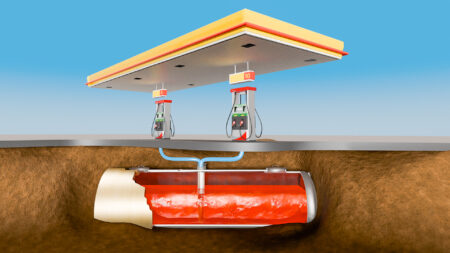

Escalator fires on the London Underground weren’t uncommon. In fact, in the 30 years before the King’s Cross fire, more than 400 had been reported.

Although smoking had been recently banned in underground stations, people regularly broke this rule, and would often light up just before getting on the escalator. Matches and cigarettes would fall between the gaps, igniting the escalators which were still surprisingly made of wood in many underground stations.

The thing is, these fires would almost always go out by themselves. So why did this one go from a small fire to an enormous inferno in just a matter of seconds?

When the investigators opened up the other escalators in the station, they noticed that a large amount of grease had built up, and according to staff, this hadn’t been cleaned in years. Normally, this grease on its own would be very hard to ignite. But after years of accumulation, the grease was full of dust, fiber and debris that had dropped through the gaps after years of operation.

The investigators tested this grease on an open model of the escalators and found that it was very easy for lit matches to fall down the gaps, ignite the grease and start a small fire. But no matter what they did, the fire would always burn vertically and eventually put itself out.

There was still something missing.

King’s Cross theories

One of the main theories was that the ceiling paint, which was 20 layers thick, had absorbed the heat, ignited and caused the fire to spread up the escalator shaft. But this went against the witness statements, which claimed that the fire never touched the ceiling at all, and instead, stuck to the escalator steps all the way to the top.

Super computer fire simulation

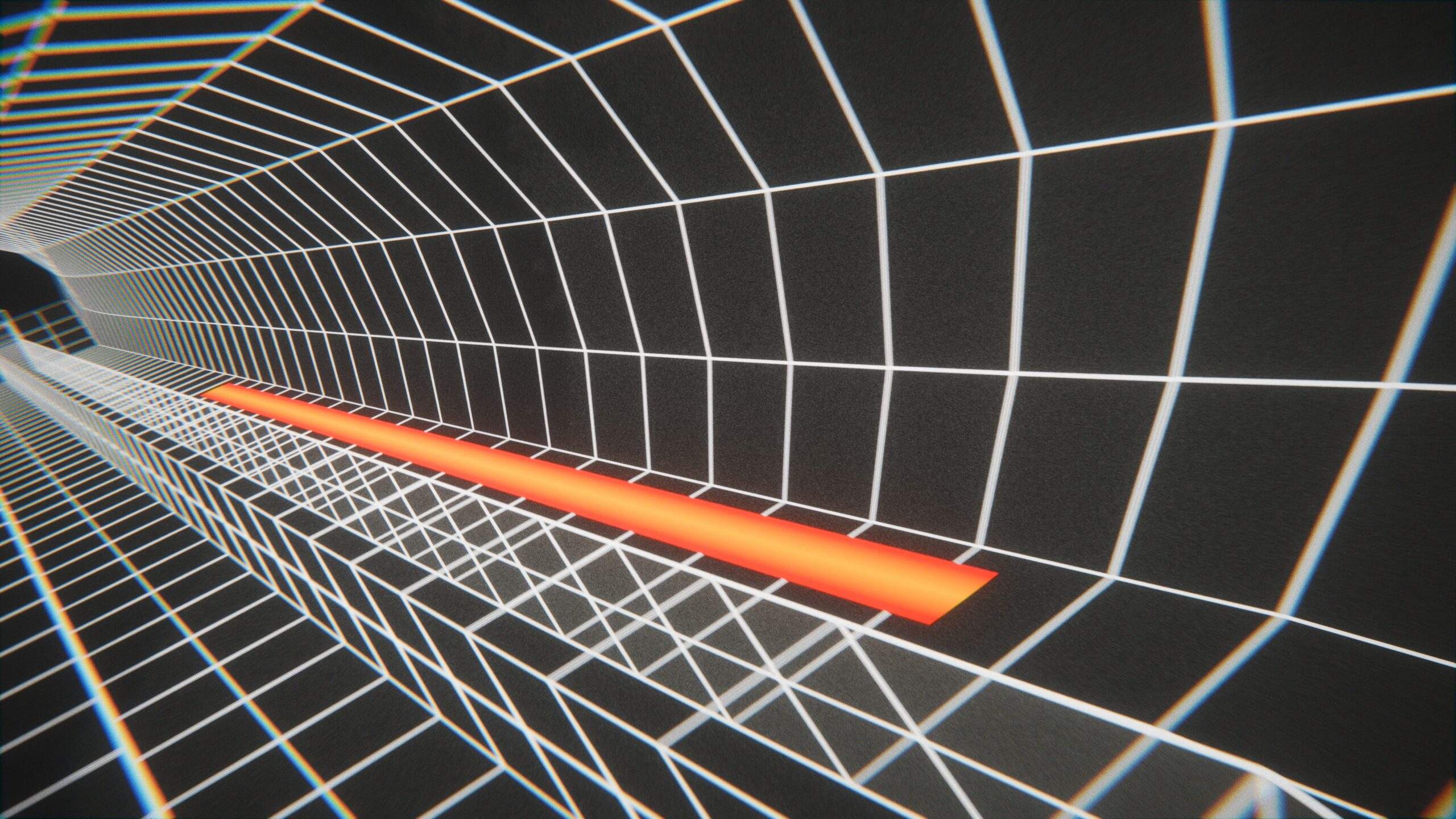

To determine whether this was even possible or not, a computer simulation was set up using the Cray 2 super computer, the only one that existed in the UK. This calculated the temperature and airflow of gas at various points, to simulate how the fire might have spread. The result was astonishing.

The simulation perfectly predicted that the flames and hot gases wouldn’t travel upwards, but instead, hug the entire length of the escalator steps. This completely defied normal fire behaviour, as you would expect the hot buoyant gases to have a lot of upwards force. Here’s what’s happening.

The Trench Effect

Thanks to the trench-like shape of the escalator shaft and its 30 degree angle, the flame couldn’t spread outwards, and so the heat had to flow in the direction of the trench.

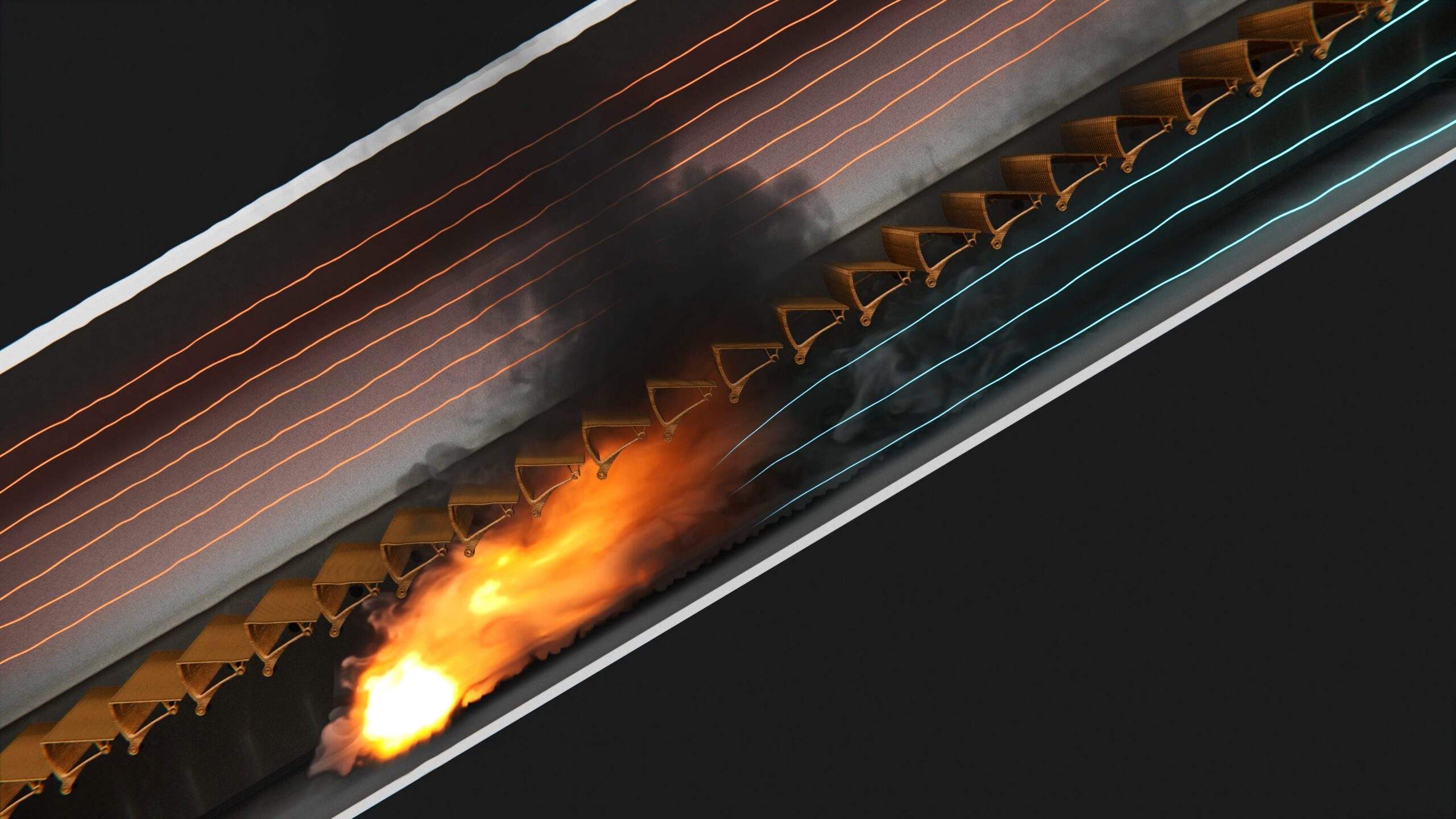

At first, some of the flames did escape upwards through the gaps, but the majority were forced to travel under the escalator steps. As this stream of hot gas accelerated up the escalator shaft, its pressure dropped, creating a difference in pressure above and below the steps.

This gradually pushed the fire over, until it started sticking to the underside of the steps. The hotter it burned, the faster it traveled and the more it stuck to the steps.

To the witnesses, all they could see was a rather small insignificant fire halfway up the escalator. But beneath the steps, the hot gases were heating the entire length of the wooden escalator to temperatures well above 500 degrees. Those hot gases were then funneling into the ticket hall, and filling up the void above the false ceiling. What happened next turned this small fire into a disaster.

Flashover

When materials reach a certain temperature, they ignite automatically, causing the fire to spread almost instantly. This is known as a flashover.

Eventually, the escalator and hot gases reached this temperature, and in an instant, everything ignited. This sent a fireball rushing up the escalator and into the ticket hall, igniting every surface and filling the place with fire and smoke.

The computer simulation had shown this exact effect perfectly, but it wasn’t fully believed until the investigators performed real tests on a scale model of the escalator shaft. At first, the fire burned upwards, but after just a few minutes, it started lying down and hugging the floor of the escalator.

This brand new discovery was named the trench effect, and it led to a bunch of new safety improvements. All wooden escalators were replaced and heat detectors were added beneath escalators with automatic sprinkler systems.